BY EMILY ACKERMAN |

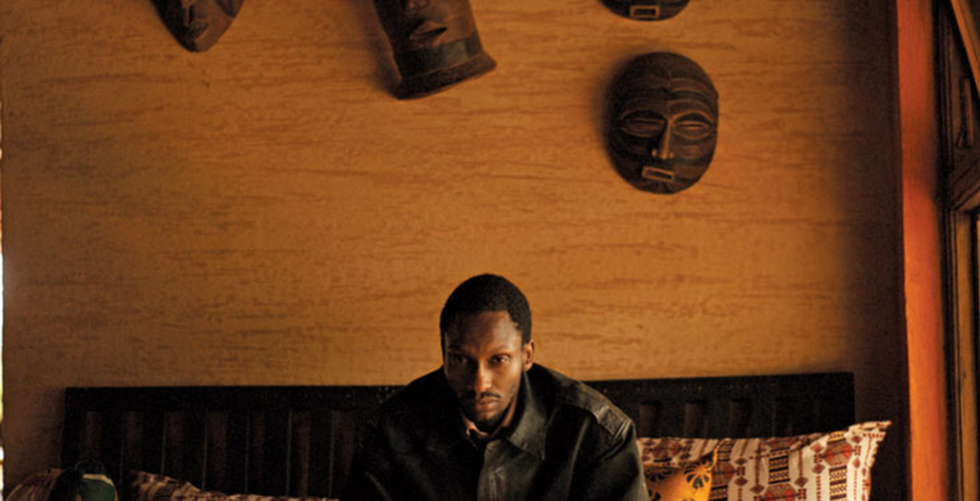

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Grey Matter

There are films about Rwandan genocide, and then there's this: not only a penetrating and artistic cross-section of a country's shattered psyche, but the first feature film from a Rwandan filmmaker... ever.

Tribeca: Tell us a little about Grey Matter.

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Grey Matter is my first feature film and its title could have been Trauma. It’s a film about the brain and the tricks it can play on people when they go through really traumatizing experiences. So it’s a film about madness and mental instability.

Tribeca: Did you grow up in Rwanda?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Yes.

Tribeca: What inspired you to tell this very personal story?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: First, I wanted to make a short film because I didn’t yet feel comfortable making a feature-length film. I had written this story about two siblings who had lost their parents, lost everything, and I wanted to tell their story first. That’s what I felt ready to do, but when I finished writing it, I realized it was not clear what had caused their pain and their loss. Then I wrote this story on the side about a madman who might have killed the parents of those siblings. So I had those two short stories and I was thinking about ways of combining them. They were too long when put together, but I didn’t want to cut anything. I tried to fundraise for both, but it wasn’t happening. People kept saying they were too dark or too pessimistic. I was seriously considering giving up. But ultimately I knew these were stories I needed to tell.

So when I totally failed to get money for either of the stories, I was stuck in a hotel in Mexico as a Festival I was attending there had been cancelled, and I asked myself, "Why I am struggling to tell these stories separately? Do I even have to?" That was when I wrote in the part about the filmmaker trying to make a film that no one cares about, and then the narrative made sense to me. Then I was ready to put it out there because the film was now about myself as well as the people that I care about.

Tribeca: Did you know you wanted to deal with the political history of Rwanda, particularly that of the genocide?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I tried not to be the filmmaker making another film about the genocide, because many already exist, but I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. They were all made by foreigners, and I actually lived through it. It’s also true what they say that in order to move on, you need to say what's in your heart. You need to tell your story and share it with people. I have so many other stories I want to tell that are absolutely not related to the genocide, but I needed to do this one first in order to be done with that chapter and move on.

Tribeca: This is also a very important film for Rwanda, as this is the country’s first feature-length film.

Kivu Ruhorahoza: There are some videos that have been made by Rwandans, and Rwandans have been involved in the production of foreign films made there, but this is the first feature film written and directed by a Rwandan.

Tribeca: How about your cast and crew on this film? Were they all Rwandan as well?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: All the actors were Rwandan. The woman who plays Justine and the man who plays the filmmaker are both professional actors who do a lot of theater. My cinematographer and the assistant director were from Australia, but the rest of the crew were from Rwanda, and they had some experience with film, but we were all beginners and learning on this project.

Tribeca: The character of the filmmaker in Grey Matter is also struggling to get a film made and seeks funding from the Rwandan government. Did you receive any funding from the government?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: No, we didn’t, which was unfortunate because I’m sure they could have found a few thousand dollars to spare. Unfortunately, people don’t understand film in my country. There is no film culture, and there is not a single movie theater. There are video clubs where someone just takes a projector and shows some DVDs, but those are not theaters. So Rwandans don’t get independent films. If I was making an action film, maybe I could have gotten some funding from the government, and I definitely could have if I’d been making a film about AIDS and gender equality, but I wasn’t. So I used my entire savings, all of it, and I got a good production deal with some Australian guys who were really supportive of me. We used whatever we had, and finally the film happened.

Tribeca: Well, hopefully your film will be a breakthrough work for other aspiring Rwandan filmmakers.

Tribeca: How did you learn about film and filmmaking?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I worked as a production assistant for a year for a Rwandan producer who does a lot of TV and some documentaries. I was then promoted to production manager, and I was assisting a lot of crews coming in for news from the BBC or CNN, but my love was film, and I wanted to write and direct. So when I felt ready, I quit my job and started writing a lot and making short films. So I learned what I know from being on set and watching lots of films. I think that’s the best way to learn about film. I’ve watched thousands.

Tribeca: So people in Rwanda don’t really watch films?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Not really, and they don’t watch independent films. They watch Hollywood films and Nollywood films. Do you know Nollywood? It’s a genre of Nigerian filmmaking.

Tribeca: No I don’t. I know Bollywood!

Kivu Ruhorahoza: They watch Bollywood in Rwanda too. I watched a lot of Bollywood when I was little. Rwandans love Bollywood and also Kung Fu movies.

Tribeca: Well, I imagine it would be quite hard for people to get a hold of independent films in Rwanda.

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Yes, but there is a film festival there that shows independent films, but people don’t care. They get an elite crowd mostly of ex-pats, and people from NGOs. If you really want to find them, you can, but have to really want to.

Tribeca: Were there any filmmakers or artists that inspired you while working on this project?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I try to avoid being heavily influenced by anyone, but when I was looking at the final version of the script, I decided to watch Repulsion by Roman Polanski, as well as The Tenant. I also watched some David Lynch films and five films by Kim Ki-duk. I love Kim Ki-duk. David Lynch and Roman Polanski’s early works really are about madness and losing it, and Kim Ki-duk has a particular way of filming women, particularly those who are losing it, who are what we call in French “sur le déclin.” My main female character in the film is disintegrating. She is really a strong woman, and still trying to fight, but life doesn’t always work out. People accuse Ki-duk of being a misogynist, but I think his female characters are portrayed with much love.

Tribeca: In your film, the lead female character, Justine, is really the only person who hasn’t submitted to her trauma and is trying to hold what’s left of her family together.

Kivu Ruhorahoza: For me, she symbolizes the Rwandese women who, after having been raped and left on their own after the genocide, decided to rebuild their families and the country. So many men had been killed, and so many men had killed those men and then fled the country. There were so many women left on their own and vulnerable, but they fought really hard to get control of their lives. That’s Justine for me; whatever she’s had to suffer, she just keeps on going and works really hard.

Tribeca: Is this state of trauma you mentioned before, and that is clearly present in all the characters in your film, still the general temperament in Rwanda today?

But now you see all these women who have been raped and lost their husbands and families and they seem normal, but they’re not. Well, what’s normal anyway? But you can’t be normal if you‘ve gone through those traumatic experiences, and these women are raising their children again and holding their families together, and I don’t know how they do it. Still, sometimes you’ll see someone bursting into unexplainable laughter, or crying for no reason, or even committing suicide because of all the things people have accumulated in their hearts. They call us the Japanese of Africa because we don’t have a very communicative culture.

Tribeca: What's the craziest thing (or “lightning strikes” moment) that happened during production?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: At one point I asked the actress who played Justine to cry, and she started to cry, but she wasn’t acting, she was really crying. I didn’t get it at first, and then when I said, "Cut," she kept crying. It was the first time I had seen this as a director, and I was really uncomfortable because I didn’t know how to react. Everyone on the set was frozen. It reminded me of a girl I went to high school with. One day we were in an exam and she just started crying for no reason and no one knew what was going on. I asked for five minutes and went into the bathroom and started crying as well.

It was a really difficult shoot because we were terribly broke, but also because the Rwandese crew and cast had crazy stories of things that had happened to them during the genocide. So there were a lot of things we were not able to talk about on set. You would see someone refusing to do something and you wouldn’t know why.

Tribeca: What was it like filming the scenes where Justine’s brother Yvan has hallucinations of what he witnessed during the genocide, such as burning bodies? Was that difficult to recreate?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I had those “bodies” made by a tailor, and when we were moving them to put them in the car people were screaming in the street. After burning them, the guard of the house where we were filming saw the flames and came out to tell us we weren’t allowed to film anymore. Someone calmed him down and told him they were not real bodies, but that was a hard day on set.

Another difficult scene to film was the exhumation in the woods. People around us thought it was a real exhumation, because we filmed it the way they actually happen, digging up all these buried clothes and bones. Some neighbors got offended during this scene as they thought we were carrying out a real exhumation. They wanted to know why we were performing this task without asking them since we were not from their area and those bodies might have been their friends and family who had been killed in the genocide. We had to tell them it was for a film and it wasn’t true.

Tribeca: Are they still discovering mass graves in Rwanda?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Yes and they probably will for tens of years.

Tribeca: So how did people react when you told them you were recreating these graphic scenes for a film?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: They were usually curious, and some of them got offended. They asked me why I was taking their stories, and I told them it was my story too. I come from Rwanda. I lived through the genocide, and I wasn’t with my family, and at one point I thought that they had died and I was the only survivor. It’s never easy to make these kinds of films, as some people think you are exploiting their losses or their misery, and in a way they’re right. If I get any success, it’s going to be me. If I make money on the film, it’s going to make me feel uncomfortable.

Tribeca: But on the flipside, this is a story that needs to be told, so that the genocide and its after effects on Rwandan individuals can be better understood.

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Yes, absolutely.

Tribeca: Have you screened the film in Rwanda?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I made the mistake of screening a first cut because I wanted see what people thought about the music. It wasn’t a good idea. I presented it as a work in progress since the sound wasn’t correct and there was no color grid, but when I gave people forms to fill out after the film I got really harsh comments back about how the color was wrong and the sound was off. The audience kind of lost the point. There was an American woman who left crying and wouldn’t speak to me for about two weeks. She wanted to know why I had made this film and what it was adding to the world.

Tribeca: Were you supposed to have made a positive film?!

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Right. Do I look like the kind of guy who is going to make a comedy?

I haven’t screened the final version anywhere yet. Tribeca will be the world premiere.

Tribeca: Are you planning to screen it in Rwanda?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Yes. I feel a little uncomfortable doing it, but I have to. I’d like to screen it in a proper theater, but we don’t have one. I definitely don’t want it to be screened in rural areas. The film festival in Rwanda goes into rural areas and villages and screens short films, but I don’t want to do that.

Tribeca: Is that because you think it would cause uproar within the crowd?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I’ve had friends who’ve shown shorts in rural areas, and one woman had a seizure at a screening, which was quite uncomfortable.

Tribeca: What’s the biggest thing you learned while making Grey Matter?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Film-wise: get prepared. Don’t use personal money, because you won’t be able pay rent and you will probably lose everything: your money, your girlfriend, everything. It happens for some people, but not for millions of others. I lost my credibility because people never saw me shooting and then we spent a year and a half in post. So get prepared and try to find someone to give you the money.

Also, your authority is challenged every minute when it’s your first feature. Sometimes you’ll ask people to do things and they will tell you, “No, I don’t think that’s such a good idea.” So it’s hard to make a micro-budget film, but it’s a good experience on the human level in terms of working with people and sharing your vision with them. I’ve worked on short films with a two-man crew, but for this film it was amazing having all these people helping me, from my editor, Antonio Rui Ribeiroto, to the actors just giving me what I needed. It was truly incredible and I’ve never experienced such a thing.

Tribeca: What do you want audiences to take away from Grey Matter?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I want them to get curious about stories of individuals from my country, not the story of the country as a whole. I know the film it is not going to change anyone’s habits, and if they watch my film and then 20 minutes later they watch an amazing comedy, that will be the end of my film in their head, but if people get curious and try to find out more about the story behind the film, that would be satisfying.

Tribeca: What’s your advice for aspiring filmmakers?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Watch millions of films, work hard on your script and get well surrounded. It you don’t have an amazing team, it will never get made. Directors get all the credit, but there are so many other people behind the scenes whose work goes unrecognized. You write your film and then you get on set and it’s like you’re rewriting the film. Then in editing, it’s like you’re re-re-writing the film. So get a good team together.

Tribeca: What are your hopes for Grey Matter at Tribeca?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I hope it will win an award or find an interested distributor so the film can have a career. I also hope to make good contacts as I’ve got many more stories that I want to make. I’ve got my second feature ready to go into pre-production.

Tribeca: If you could have dinner with any filmmaker (alive or dead), who would it be?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: Well, Kim Ki-duk. Also, Pier Paolo Pasolini. And Cédric Kahn, because his film L’ennui was so important to me that as the credits were rolling, I knew I decided to become a filmmaker. Also David Lynch, Jane Campion, Takashi Miike, Paul Thomas Anderson, Gus Van Sant, and The Coen Brothers. I’ve watched Fargo hundreds of times.

Tribeca: It’ll be a dinner party! What piece of art (book/film/music/TV show/what-have-you) are you currently recommending to your friends most often?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: An amazing book called The Possibility of an Island by Michel Houellebecq and Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

Tribeca: What would your biopic(s) be called?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: I live at night so it’s got to be something in relation to the night. It’s my element as I’m so uncomfortable during the day. “Indoors” maybe, or “Night Shift.”

Tribeca: What makes Grey Matter a Tribeca must-see?

Kivu Ruhorahoza: It’s a different film. It's original. I felt honest when I was writing and directing it and an honest film is always different, isn’t it?

Also, I don’t like selling myself as an African director, but you won't get to see many African films. Grey Matter is one of the only films in this year’s Festival made by an African filmmaker [the three directors of Perspective: Rwanda are also Rwandan], so I hope people will come see it and get curious about African filmmaking.

Find out where and when Grey Matter is playing at the Festival.

Check out Grey Matter's Official Website.