BY MATTHEW ENG |

A Heroine, Rediscovered: David France on THE DEATH AND LIFE OF MARSHA P. JOHNSON

Marsha. P. Johnson helped set off a revolution. Now, nearly 25 years after her mysterious death, her under-recognized legacy is vividly reclaimed in an essential new documentary.

Marsha P. Johnson remains a hero seldom referenced in the history books. There are no buildings or boulevards named after her, no grand-scale biographical dramas charting her life, work, and achievements. In fact, her achievements often go as unrecognized by the larger American public as her very name.

But David France, director of the upcoming documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson, refuses to let such ignorance persist. Like his Oscar-nominated debut How to Survive a Plague, France’s latest is a bracing, restorative, and impeccably-researched work of artistic activism, centered around Johnson, the trans pioneer who fearlessly took her place at the vanguard of New York City’s LGBT movement in the 1960s.

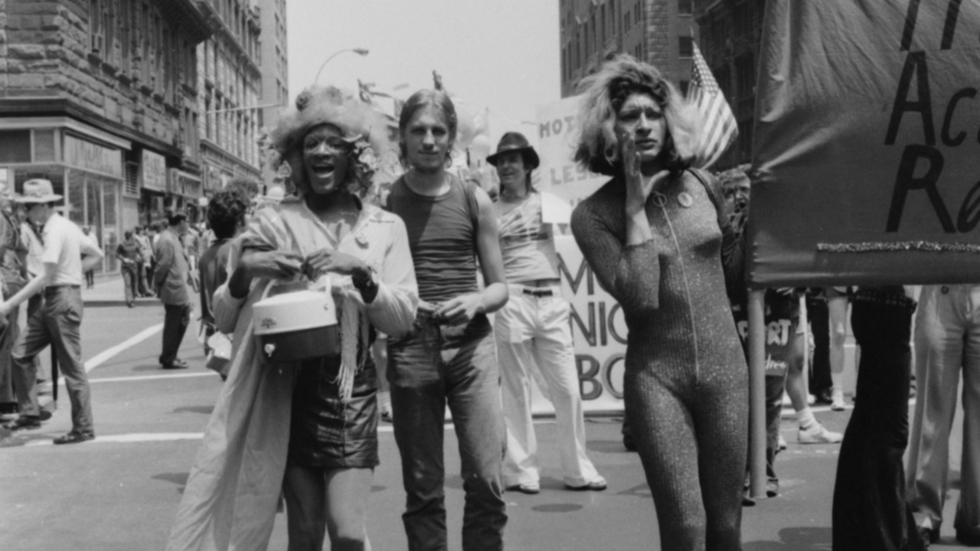

In July of 1992, Johnson’s lifeless body was found floating face-down in the Hudson River. Her death was swiftly ruled a suicide by the police, but that judgment has never sat well with the friends and fellow community members who knew the vivacious leader best. That includes Victoria Cruz, a crime-victim advocate for the New York City Anti-Violence Project who teamed up with France to shed light on the suspicious yet thorny circumstances that led to Johnson’s death. Cruz is the driving force behind France’s film, which does a thorough and thrilling job of reviving and retracing Johnson’s legacy, as well as that of Cruz’s close friend Sylvia Rivera, the trailblazer who boldly stood beside Marsha at the frontlines of the fight for trans rights and fell in and out of destitution throughout her embattled but intrepid life.

In this way, The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson functions as both a vivid historical chronicle and a three-pronged character study of Johnson, Rivera, and Cruz, a courageous survivor and fighter who frequently lets her own guard down as France films her dogged search for clarity. Along the way, Cruz hits wall after wall but also makes new, integral developments in this forgotten case, all captured in a film whose very existence is a deep and humbling triumph.

“My mission in my filmmaking is to tell queer stories as American stories,” France tells me near the end of our interview, a little more than a week before his film’s world premiere at this month’s Tribeca Film Festival. By treating the efforts of Johnson, Cruz, and their often marginalized comrades not as a footnote to American history but as American history itself, The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson is a clear-eyed affirmation of France’s mission, as well as a rightfully infuriating and ineffably moving cinematic experience. But it’s also a pathway, leading into a region of American history far less chronicled but brimming with stories that must be known.

I talked to France about the film’s inception, its classical influences, and what Johnson can teach us in these precipitous times.

How to Survive a Plague was your directorial debut. I know you had worked in the film and TV industry in some measure prior to this, but you had primarily made your name as an investigative journalist and author. Did you always know or even anticipate that you would continue making documentaries after Plague?

I think it’s fair to say that I had film aspirations. But I had never really had an active role in any of the [film] projects that developed from my work. So I had three films that were made based on my journalism, developed from articles or books that I had written. But the role that I played is the role that source material providers always play in these situations, which is absolutely nothing. I was able to find in one script that they had made a mistake. And I had to point that out to them, meriting my executive producer title.

So I had never really made a film until 2009 when I began to try to write a book about the AIDS plague years. And it was a very bad time in publishing and I had failed to find a publisher. Nobody was interested in it. And there was a belief at the time that the story of AIDS had been told. I kept saying, “No, it [hasn’t] and if you think you know the history of the plague years, you’re mistaken.” So, deprived of a publishing outfit, I went to a video tape archive to see if I could do something [visual]. I thought, Nobody can stop you from making a documentary film — which, at the time, I thought was part-time work. I thought it would be done in a couple of weekends and I’d have a film. But it took me a couple of years — three years. And it was a medium I had never worked in before, but it was also really fun. I’m a long-form non-fiction writer, which means you spend a lot of time alone in a room going through your notes and compiling your manuscripts. It’s really lonely work, which I had never felt lonely about until I started working on a documentary, which is so collaborative. And it thrilled me. I was so thrilled with the process and had so much fun that I decided to try it again.

How did you get involved in this particular project? I understand you share something of a personal connection to many of the subjects covered in the film, including Marsha.

I knew Marsha. She was one of the first people I met when I moved here from the Midwest. And I had a boyfriend at the time who was very worried about my ability, as a young Midwesterner, to survive the rigors of life in New York City. He was giving me a sort of bootcamp training on what I’d need to survive and one of the first people he took me to meet was Marsha. She was here in the East Village hanging out in a semi-abandoned storefront. We walked in and there was this remarkable, technicolor creature. And she was selling fake tokens for the subway. She called them “sequins.” And you could get a bag of these fake tokens for five bucks and that bag would last you three or four months, which was something you needed to know in order to survive in New York. And so I became a regular customer of Marsha’s. And, of course, I took my place on Christopher Street, which is what every young, gay man did at the time. And she was there every night. Like, every night. We weren’t friends, we didn’t take meals together. But she embraced me and gave me a home in queer New York. So I always felt beholden to her for her generosity.

I was at The Village Voice in 1992 when Marsha died and I was asked to do an investigative piece around her death. And I just never did it. So I always felt there was unfinished work, my unfinished work. And I didn’t do it because 1992 was such a turning point in a very bad way for the AIDS epidemic, in terms of the number of people dying. Multiple people I knew died in 1992. My lover died in 1992, shortly after Marsha died. So I was taken over with grief and all that that entails. And, as a result, nobody did the reporting. Nobody did the investigation into whether or not a crime had been committed when it came to Marsha’s death. But it has always weighed heavily on me that I didn’t do it. When I started realizing how much fun I was having making How to Survive a Plague, I began making notes about other stories from the queer canon that I might want to lift up. And Marsha’s story was there.

When did Victoria join the project?

Victoria came onboard in January 2016. I was looking for an approach, a way into this story. I wanted to tell the story of Marsha and Sylvia as the origin of the trans movement. It rightfully is that. And I wanted to do this investigation but I didn’t want to do it myself, on-camera. So I went to the Anti-Violence Project, which had been the lead agency in 1992 investigating, for the community, what might have happened with Marsha. I went to them and said, “You have these files. Would you revisit them?” They said yes. And Victoria was the person with the greatest interest in doing it.

Was she immediately onboard?

She was immediately onboard. Of course she knew who Marsha was. She and Marsha weren’t friends, but she and Sylvia were. And they were fast friends. Sylvia went to her grave upset about Marsha’s death. In a way, Victoria felt she was lifting up the responsibility from Sylvia after she died.

The film is called The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson and the central narrative revolves around Marsha’s trailblazing life and tragic death. But the scope of the film is so much more expansive than a single individual and stretches to encompass so many people, experiences, and periods. Did you come into the project knowing you wanted to create this wide-ranging panorama in addition to a character study or was this dual approach something the film naturally grew to adopt?

I knew I wanted to do both. I kept calling [the film] “the origin story of the movement.” I wanted it to show the grandness of that work and how Marsha and her partnership with Sylvia really began this revolutionary movement in the way we understand gender. [They] really changed everything. They were the first to conceive of it. That’s what made them important. And that’s why we should care about what happened to Marsha. So I knew that there was going to be a tension between those two [elements] but I wanted to tell that historical story through the language of genre. I wanted to find a way to not make it a history lesson. I wanted to make it film. With Victoria, we have this wonderful investigator. She’s dogged, she’s clever, she’s fearless. And she’s also great to look at. She thinks in such apparent ways that you can see it on her face. And we started seeing the film as this sort of film noir, almost a whodunit. And Victoria gave us that, she taught us that. So we went along with her on that journey.

In terms of styling this film as a whodunit, did you turn back to any films from that genre or was it more of a subconscious influence?

I turned back to all the noir films to see if there was language in there that would work. We used a lot of the visual language. The film is shot mostly at night and in the rain. So there’s an atmospheric quality to the way we’re entering the story that carries you through these familiar tropes while you’re discovering the lives of these incredible, transformative women.

Victoria and many of the women who are featured or interviewed in the film speak about their often difficult, even traumatic pasts with a candor that surely required a unique level of comfort and trust between themselves and you, the filmmaker. How did you encourage them to open up in front of the camera? Did you face any resistance?

Victoria was resistant at first. She thought, Who are these people? Why should I be paying attention to what they’re interested in? But then she agreed to meet and we just had such a wonderful meeting. She’s a remarkable human being, she really is. I think, it’s fair to say, we fell in love. And we’re still wildly in love. I think you can see that on the screen. But it was she who opened everyone else up. She didn’t know those people. Some of them may have heard of her and the work that she has been doing in responding to crime. I mean, she’s not a crime-fighter. She’s a victim advocate. But when she sat down with [these people], they just sank into her. And you do see that. You see that when she goes to talk to Kitty Rotolo [in prison]. And in her final scene with Marsha’s roommate, where she really turns his head with what she has found. The stuff that she discovered broke his heart and he believed her and felt that and responded to her. That’s true of everyone we encountered.

There are so many people Victoria met along the way during her investigation who we couldn’t get into the film. We just couldn’t. It was painful to remove people who were so important in Marsha’s life and who the audience would just adore. But we had to make it a manageable size and keep it as thin as movies typically are, while allowing all these other threads as you connect this in-depth celebration of a movement to an analysis of what remains as challenges for the movement.

Beyond the present day footage, you have accumulated such a wealth of archival footage in order to chronicle the history of the trans movement, ranging from news footage to home videos and beyond. It seems like such an overwhelming process from the outside. I’m really curious about how you went about compiling but also assembling these vital materials.

I had a really great team working on this at the beginning, a mostly young team. And we used the tools of journalism: the idea that we don’t take “no” for an answer, the idea that our instincts as researchers can’t be deterred. And we found footage that no one has ever seen. And it was hard to do. As famous and significant as Marsha and Sylvia remain, we found that most archives don’t list them. They were listed as “drag queens” or “transvestites” without names. When we discovered that, we realized we really had to dive deep, which we did. The quantity of footage that we went through in proportion to what we discovered is enormous. It was a large haystack we built in order to find what we found.

Which clips were new to you? Were there any that particularly astounded you?

I think all of them are really stunning. We didn’t know about the interview that was done with [Marsha] just before she died, in which she talks about her fears of death. And that’s a piece of evidence. It’s not just a great scene in the film. It changed the direction of our research and our investigation into what might have happened. And that was very startling.

One of the more polarizing but utterly critical arguments raised in the film is that transpeople are still being left out of the ongoing fight for LGBT rights, even though transwomen of color are continually targets of violence, exemplified here by the late Islan Nettles. There are many prominent members of the LGBT community for whom trans equality is a non-issue. How important was it that your film bring this matter to the fore?

We kept saying, right from the start, that this is a movie about the fact that so much has changed and so little has changed. We know it from the statistics that transwomen of color are experiencing epidemic levels of violence. And other things. Young transwomen of color make up the largest growth population among new HIV infections. They are the least connected to healthcare of all Americans. It is an extremely marginalized community. And we realized that there was a natural tension between our desire to find out what happened to Marsha, an old cold case, and our desire and need to bring attention to what’s happening on the ground today. And that tension plays out in the film. It wasn’t just a filmmaker’s idea to do that. That’s the reality in the movement and in the community. At first I thought that what we were looking at was a story about criminal justice reform. Our assumption was that Marsha’s case was blown and that what we needed was better prosecution and police work. It just became clear very early on that the violence and the problems are much more systemic. And that’s what the film is about. The system in place has made itself so impenetrable for the trans community and especially transwomen of color. Organizations responding to crimes against them can’t raise money to adequately [help] and then those organizations become isolated from the rest of the LGBT community. As a result, it puts [transwomen of color] further and further away from the fabric of American civic life. These more enormous problems are exposed, I think, through the vehicle of this investigation.

What are your own views on the LGBT movement now?

We don’t know what’s happening in the current political environment. We know it’s going to be awful. And we know everyone in the Trump cabinet has solidly anti-LGBT backgrounds. Oh my god, there’s so much that needs to be done.

Do you think there’s anything specific we can learn or take from Marsha at this moment?

As significant as Marsha was in her role building the foundations for the modern LGBT movement and the formation of the first transgender rights group, she had adopted a posture of… happiness — as a political tool. She fought for freedom and power by acting free and powerful. And in that way, she represented that for others in the movement at a time when no one was imagining what that might look like. She put it on. And she said, “This is what freedom’s going to be like.” And I had never seen anything like that before. You certainly see it in the footage of her: the power she had to advance an entire people by wearing a silly costume and staying just above the fray. Sylvia was much more direct and surgical and acerbic and demanding. But it was really Marsha who moved things forward. That’s a lesson I think we can all learn from today.