BY MATTHEW ENG |

Both Sides Now: On the Politics of Representation in Gillo Pontecorvo’s THE BATTLE OF ALGIERS

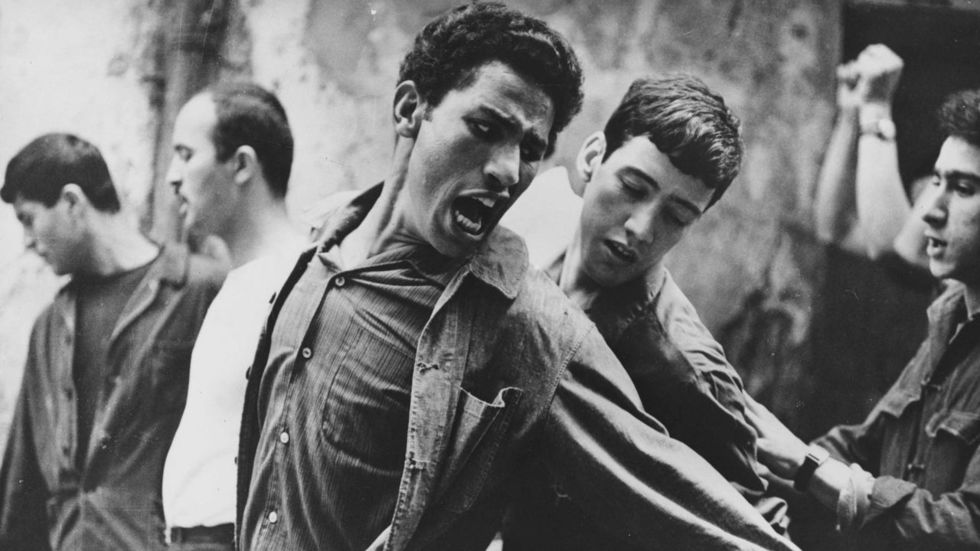

Fifty years ago, Gillo Pontecorvo's legendary political thriller humanized "the enemy" and changed cinema forever.

Few films have incited more worldwide fervor upon their debut than Gillo Pontecorvo’s thematically provocative, passionately-made, and politically-minded The Battle of Algiers, which turns fifty this September and has certainly proven that even the most enduring cinematic masterpieces can live just as much in inflammatory international infamy as they do in complete critical renown. Beset with an unavoidably difficult production and an even more contentious global reception, The Battle of Algiers was banned in France for five years upon its initial release in 1966 for daring to not just humanize but boldly and unequivocally identify with the Algerians who for eight years (from 1954 to 1962) fought violently, vehemently, and — in the eyes of many Europeans — terroristically against French colonization during the Algerian War for Independence.

From its opening disclaimer, which swears that “not a foot of this film is newsreel footage,” The Battle of Algiers reveals itself to be a staggering and still-unsurpassable cinematic achievement, a naturalistic recreation of events still blisteringly fresh in the public consciousness that has unquestionably influenced every wartime drama that stands inside its long and steadfast shadow. Shot on the very streets where the Algerians disrupted one-hundred-plus years of French dominion, Pontecorvo approaches his account with a documentary aesthetic that maps out this urban battle space with dazzling exactitude. The Battle of Algiers is still one of the only works of war cinema that thoroughly understands the architectural character of a city in combat, at once meticulously structured (through checkpoints, barriers, and routine patrols) and conspicuously impromptu (through the increased presence of bombed-out structures, burning cars, and rubble piles). The familiar layout of Algiers, with its automobile-lined boulevards, neoclassical structures, and wide open spaces, begins to readjust before our very eyes into an arena of chaos, debris, and collateral casualties. Watching the film now, after so many other popular films and latter-day television series have faithfully duplicated its look and feel, it is all too easy to take for granted just how revolutionary a filmmaking document Pontecorvo had created, a visual groundbreaker made all the more monumental for the atypical coherence of its storytelling.

Unlike so many of its unstable clones and frequent imitators, The Battle of Algiers is in no way a puffed-up piece of ripe, rip-roaring propaganda, much unlike the juicy macaroni combat exploits that emerged from Europe at the same time as Pontecorvo's neorealist examination of warfare and all its costs. And its focus is never strictly limited to the endeavors of one side — in this case, the Algerian freedom fighters and their radical retaliation against oppressive occupation and the local crises such occupation incites. The centralized focus on the Algerian anarchists surely clarifies where the film’s political sympathies lie, but Pontecorvo provides almost equal emphasis on the strategic efforts of the French servicemen who fought against them.

These colonial soldiers are not merely leering, desensitized villains, a vein of depiction to which a more slanted film would likely yield. Led by the clever, unruffled pragmatism of Jean Martin’s Colonel Mathieu, the paratrooper commander who is unquestioningly intent on upholding France's rule and fully aware of the fatal sacrifices that must be made to do so, these men and their larger hierarchy are portrayed here with as much dimension and credibility as the main Algerian unit. Pontecorvo’s writerly inclination to probe both sides of this conflict — and retrieve so many complex insights from each — ensures that The Battle of Algiers is a rounded, multifaceted experience that further serves as a well-timed challenge to viewer empathy. There simply isn’t a rah-rah bone in Pontecorvo’s body, even though the film by no means derives from political neutrality.

By placing the audience in the Casbah tenements and clandestine communal meeting places where the National Liberation Front’s key leaders scheme and strategize, but also on the frontlines and in the anodyne war rooms where the French servicemen do the same, Pontecorvo draws a clear and direct line from one group’s battle methods to the other diametrically-opposed group’s similarly-hatched tactics, depicting each with the same level of particulars and precision. That the Pentagon famously screened the film for its generals during the early, escalating days of the Iraq War in 2003 is more indicative of Pontecorvo’s even-handedness in fleshing out these embattled sides with true and detailed consideration of their stances, stratagems, and beliefs than it is of any dismaying political leanings on the director's part.

Pontecorvo is clearly stimulated by the organizational methods of each camp, which is what surely made the film required viewing for the woefully disorganized Bush administration. But he also takes time to personify these methods, from Mathieu’s coolheaded command to the occasionally neurotic yet unwaveringly committed attempts of the Algerians, transporting each to the screen with similar verve. Pontecorvo is ultimately just as eager to show us the absorption of Brahim Haggiag’s petty thief Ali La Pointe into the FLN — and the build up of retributive bloodshed that follows thereafter — as he is to let us observe Colonel Mathieu sermonize on the art of war and devise the best line of defense against the early pushes of violence. Pontecorvo sees each man as a fully-formed human being, not a rhetorical figure of supremacy and suffering or heroism and criminality, and therefore undoubtedly worthy of our extended time and engrossed consideration.

It is this same humanist quality in Pontecorvo’s writing and direction, however, that ultimately informs the film's political convictions, which fall decisively in favor of the Algerians’ struggle during the picture’s extraordinary end. After a sobering, dread-inducing climax, in which Ali and his comrades are found and annihilated by Mathieu’s faction, the film concludes on a sequence of ululating, flag-waving Algerian women as they take to the streets and wail in the faces of the increasingly outnumbered French forces who try to quell them. In this moment, The Battle of Algiers manages to transcend the dual nature of warfare and become, indelibly, about something much more humbling: the power of the masses. This remains, without question, one of the most stirring and incomparable endings in film history and a far-reaching declaration, from Pontecorvo and the Algerians, that liberation is both impending and imperative.

A new 4K restoration of The Battle of Algiers will play the 54th New York Film Festival on October 1st, before beginning a limited run at Film Forum.