BY ZACHARY WIGON |

Interview: Michel Gondry, Tireless Innovator

Michel Gondry's latest act of reinvention? Animating a doc with one of the country's leading intellectuals.

Michel Gondry has continually pushed his craft as a filmmaker forward, never content to rest on his laurels - even though his laurels made him internationally renowned as one of the great visual stylists of the modern era. While Gondry's whiz-bang stylistics brought real vitality to films such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and The Science of Sleep, he's recast himself in different forms as of late, directing low-key narratives (The We And The I), making a doc about his aunt (The Thorn in The Heart), and, most recently, making an animated documentary film out of an extended interview with Noam Chomsky, the brilliant linguist and political theorist.

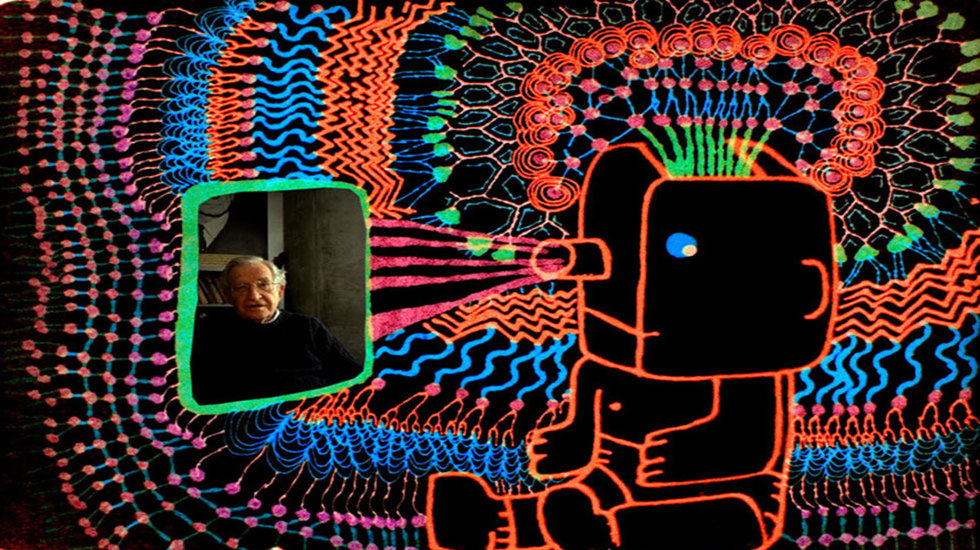

A dazzling meeting of two extremely stimulating minds, Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy? presents a formidable creative collision. Consisting almost entirely of a conversation between Gondry and Chomsky, the doc becomes cinematic through the animated visuals, which Gondry uses as correlatives to the ideas in Chomsky's thought. Chomsky being as complex a thinker as he is, the corresponding visuals are nothing less than trippy, and Gondry's interpretation of Chomsky's theories places the film at an unusual nexus between intellectual and dreamlike.

At a moment when independent film budgets are low enough that filmmakers need to constantly be considering ways of reinventing themselves, Michel Gondry points a compelling way forward. I recently sat down with Gondry to discuss the new work.

Tribeca: At what point in the process did you decide that you wanted this film to be an animated film?

Michel Gondry: That was the starting point. It was the only way I thought I could make a contribution to his discourse, through abstract animation. I didn't think I would have another way to express my feelings on his thinking. That's why I shot him on the Bolex, I couldn't shoot him all the way through, just glimpses. I didn't want to do a typical documentary - it's been done on him already.

Animation has something honest about it, because people know that what they are watching is already an interpretation.

Tribeca: Is there something too contrived about just shooting the conversation? You mention early in the film that live action presents the illusion of reality, whereas animation has no pretense.

Michel Gondry: I didn't really delve into the political aspects of Chomsky's work, but there is a way to expose reality as manipulative. In some movies you manipulate the audience into feeling how you want them to feel. I think animation has something honest about it, because people know that what they are watching is already an interpretation.

People forget they're watching a point of view when they watch a live action film.

Tribeca: So are you saying that animation is no less manipulative than live action, but it's more apparent in its manipulative nature?

Michel Gondry: Yeah. And therefore, it is less manipulative. Because you see it. It's like if you do a drawing of a scene, people know that's your point of view. People forget they're watching a point of view when they watch a live action film. If you would just translate a full interview without cutting, then you would think it's what the person is saying. But you have to dramatize a bit, you have to reorganize things in some way. But live action, when you watch it, you aren't thinking about how it's been reorganized.

Tribeca: Right. It also makes me think of how, when you're watching a live action narrative film, you are aware that you're watching fiction. But when you're watching a live action documentary, you're not aware that it's constructed. So I wonder if you think live action docs are even more false than fiction films.

Michel Gondry: They can be. When you say you're doing a documentary, it's like when you say a movie is based on a true story. It feels as if you're just asking people to go in with no skepticism. So they're very vulnerable, they absorb what they see as being the truth. So they're not going to doubt it, it's not like they're following a dream or something crafted, they believe it's the truth. So if you manipulate the truth then, you're being dishonest with the audience. I'm not saying I'm always the most honest person, but sometimes I've felt I was a bit fooled by documentaries, because you realize, oh okay, they hid this thing in the doc, something known, because it's more dramatic to hide that fact. So I feel betrayed when I find that out.

Tribeca: Perhaps there's something, when you make an animated film like this, where you force the audience to come to their own conclusions about the film as opposed to simply following it.

Michel Gondry: Yeah. I felt that I couldn't really explain or illustrate everything he was explaining to me, so that's one of the reasons why abstract animation was more accurate, because it gave room for different interpretations.

Some of (Chomsky's) writings are pretty hardcore.

Tribeca: What was the process like, of coming up with the corresponding visuals to the interview?

Michel Gondry: Well, I started with my first inspiration. The tree was first. When he spoke to me, I imagined that image. That led to this moment where I tried to express my point of view, that illustration comes earlier in life than reality, and then he and I had this misunderstanding in the conversation. So those were aspects of the documentary that showed themselves at the early stages - explaining his theories with abstract drawings, leading to a funny illustration of what was going wrong in the interview, our misunderstandings. I used those tropes in different parts. Also, when we talked about his memories, it was fun to illustrate him as a little boy. So it was fun to alternate between those different kinds of animation, abstract and more narrative. Basically, the film is presented in the order of the interview.

Tribeca: I found that some of the concepts were rendered easier to understand with the visuals.

Michel Gondry: Yeah. Some of his writings are pretty hardcore. You need to have a background. You can follow the introductions, but then when he goes deeper, like any scientific work that's complex, it's hard, with me, with my memory - for instance, when he puts words into equations - for me, I always have to come back in the chapter to find out what it means. So I felt like that was the kind of thing I could do a nice animation for, to try to show the geometric aspects of his concepts and make them stimulating and easier to digest.

Tribeca: A portrait of Chomsky as a man comes across during the film as well. What was it like for you, to observe him as a person as he discussed his work?

Michel Gondry: I found it very humanizing. He was very friendly, spoke about his children a lot, he's very attached to kids. He spoke about language and the way kids acclimate to language. He spoke about his wife a lot. That was important to me because sometimes people dismiss his views because he seems a bit hardcore. I find his ideas extremely challenging and good for the world. I found that maybe it would help people to pay more attention to his discourse if they saw him more as a warm person.

Tribeca: How did you become interested in his work?

Michel Gondry: I watched Manufactured Consent and Rebel Without A Pause. Great documentaries on him. I was very quickly convinced of his integrity. He opened doors in my mind. Then I realized he was a very important scientist. I realized there was a parallel between his scientific approach and his political approach to the world. People would say that maybe his political approach is not so subjective, but I think in politics he comes from the angle of proof, specific data. I think when people talk in the news, the source is very important. It's parallel with when you depict a scientific experiment, observation is very important, you must confirm the theory with observation. There is a confrontation between observation and theory. I think Chomsky has real integrity in his political observation. You don't have many people in politics who have a regard for science. And most scientists have a very simplified and general way of looking at politics. I think it's rare to find someone who has both in the world, someone who doesn't use a bullshit philosophy to bridge the science to the politics.

Tribeca: Was there a particular concept in his linguistics work that you were interested in exploring?

Michel Gondry: I read books of his on creativity, which interests me a lot, how it comes to the mind, how it's something we all share. I was very challenged and interested in illustrating generative grammar - how he came to it, how he would describe it - with abstract graphics.