BY MATTHEW ENG |

Home Movies: Filmmaker Phillip Youmans Talks His Tribeca Winner BURNING CANE

Get to know 20-year-old, history-making filmmaker Phillip Youmans and his haunting, Tribeca-winning feature debut Burning Cane, now a two-time Independent Spirit Award nominee.

In New Orleans native Phillip Youmans’ revelatory Burning Cane, the actions of three deeply fallible adults in rural Louisiana coalesce to form the future of a young boy named Jeremiah (Braelyn Kelly), who serves as silent witness to the mistakes and misfortunes of his despairing father Daniel (Dominique McClellan), his righteous, stoic aunt Helen (Karen Kaia Livers), and the alcoholic Reverend Tillman (Wendell Pierce), who commands reverential compliance from the God-fearing congregation already in thrall to his every word.

When Burning Cane screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in April 2019, Youmans, at just 19 years of age, officially became the youngest director to ever premiere a film in competition at the festival. Days later, his homegrown feature debut nabbed three jury prizes, including Best Actor for the mighty Pierce, Best Cinematography for Youmans, and the Founders Award for Best U.S. Narrative Feature, making its writer-director-cinematographer-editor-producer the first African-American filmmaker to win the festival’s top prize—all before Youmans had even finished his freshman year in the Film and TV department at NYU Tisch School of the Arts. Following this history-making hat-trick, the film was picked up by Ava DuVernay’s indie distributor ARRAY, which gave Burning Cane a theatrical release this past November before bringing it to Netflix, where you can watch it right this second. The film is nominated in two categories at this Saturday’s Independent Spirit Awards: Best Supporting Male, for Pierce, and the John Cassavetes Award, honoring features made for under $500,000 and given to the winner’s writer, director, and producers.

Though his roving eye for the wonders of the natural world and intricate play with multiple perspectives have earned Youmans comparisons to everyone from Terrence Malick to William Faulkner, Burning Cane is ultimately its own creation, one that alludes to the formative work of prior masters in order to compose a filmic language utterly unique to Youmans’ milieu and the characters who navigate it at their peril. No matter which way one measures Burning Cane—visually, sonically, narratively, thematically, grammatically, representationally, epistemologically—it remains an achievement of great risk and even greater artistry that is unlike anything else being attempted in American independent cinema today. The regionally-specific splendor of this drama is only heightened by the solemn urgency of Youmans’ interest in initiating thorny but necessary conversations about religion’s role in the lives of African-Americans. His film offers no cut and dried solutions or feel-good bromides but instead coaxes viewers to contemplate the lives, forces, and institutions that reside onscreen and off.

I talked to Youmans by phone in January about the origins of this rare and remarkable work, the chance encounter that led to Pierce’s casting, taking Tribeca by storm, what he has learned from the luminaries who helped make Burning Cane possible, and where he goes from here.

What are the films that made you want to become a filmmaker?

If I’m thinking back and being honest about the films that really, really spurred me on to wanting to move to the other side of the camera, I’d say gems like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Se7en… I know Goodfellas is one of them, for sure. Taxi Driver. Apocalypse Now. 2001 I’d say is probably the first one because it’s the first film that made me view film in a less sort of rigid context, in terms of story. It was a film that didn’t move in a traditional three-act structure. It was a film that, in a way, was just kind of an experience and less a story told… and I think that opened the entire [medium] to me. I look at that in terms of Burning Cane, which is more of a slice-of-life, fly-on-the-wall experience, as opposed to a beat-for-beat, catalyst-driven story. It’s not pushed forward by its plot. If anything, it’s pushed forward by mood and characterization more than anything else.

Do you feel that’s the type of filmmaking you gravitate to—less narrative-driven, more fragmented and true-to-life?

Yeah, I’d say that, definitely, definitely, definitely. I love the moments [in a film] where we’re just breathing and living with people… Sometimes my taste in films differs from the films that I feel compelled to make. It’s interesting how that can sort of divert. But I think, all in all—and especially as I look towards my next project—I do want to explore and experiment more with storytelling structure, and still recognize that there is power to providing an inkling or motivation for a character to do something. There can be some event that catapults them, without necessarily thinking about it in a beat-for-beat, this-happens-on-page-this, this-happens-on-page-that way. That can be a little obstructive. But I do think that as I grow and get better as a filmmaker, I want to consider the process of plot evolution more.

Can you tell me about the moment that you knew you had to put words to paper, pick up a camera, and tell the story that is Burning Cane?

The moment where I felt this whole thing was a real possibility started with my professor at the time, a guy named Isaac Webb. He was my instructor at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. And when I brought him the short script for the film, he read it. He felt like it was grounded in character, limited in terms of location, and could be made with the resources that I had available to me at the time, given the school. And after he made it feel like an objective possibility, it felt like… Why not? Why not take that jump? Why not take that chance?

After that I went to my producer Mose Mayer, who’s also my best friend in the whole wide world. I went to his house and I remember he was swimming in his pool in the backyard and I was just sitting on the side, kicking around the idea. And then we both came to the conclusion that, heck yeah, we were about to do this. We’re going to go through with this. There’s no reason we shouldn’t, you know? Because if we do it and finish it, if it works out, it could be something legendary, we felt. We had that sort of mindset.

I went to write the script. It took me a week or so to finish a very, very, very rough draft, an 80-page script. And then after that, I fine-tuned it after reading it with Kaia, who was initially supposed to be our casting director, but after she read the script, she said she wanted to be Helen. And she was amazing. She was the first person we locked down and then I was workshopping it with her, Webb, and Mose. All the while, we were raising money. I was putting money aside from my job. I had money from Indiegogo, like $1,500 that Mose and I raised, which meant a lot. And then my family contributed, Mose’s family contributed, some of my old teachers contributed. We were really just pooling in these resources. We never had an excess amount of funds. We never had money to blow. But we always had just enough to get by, just enough to get to the next day. And, really, that’s all we needed.

So much of Burning Cane’s narrative is told not in dramatic episodes but immersive moments of everyday people living their lives that build to a surprising climax, which is truly rare to see, even in many independent films being made today. How did you determine the shape of this story and how these specific characters came to enter its world?

The characters were rooted in my experiences with my family in Lowcountry South Carolina. The church that you see in Burning Cane is very, very akin to the church in Hampton, South Carolina, where my entire family went: Huspah Baptist Church. We would always go to Huspah when I was visiting there for Christmases or Thanksgivings. It was always the church we would go to. When we were in New Orleans, we were always going to church too.

But the characters are really rooted in my family. Helen is really the spitting image of my grandmother in a lot of respects: the language that she uses, her fierce independence, and tendency towards isolation. Daniel is an extreme of some of the emotions that I was feeling, like if you took those emotions and [put] them into a violent, toxic, masculine context. I had dealt with jealousy in a relationship. I had dealt with feeling a little bit inadequate and falling victim to the toxic masculine feelings of not being a jock, not being muscular, not being all those things that don’t really matter. Daniel was a translation of that, albeit to a much harsher context, given that he has a son that he has to take care of, given that he is a grown adult with grown adult responsibilities.

And then Tillman’s incorporation was so interesting. I read this story about a pastor who beat his wife with a two-by-four and then the entire congregation didn’t say anything about it. And I felt like that was such a blatant statement in itself—this holy figure doing such a vile thing and the rest of the congregation not saying anything about it. To me, that was insane, and it pushed forward the image of Tillman, this person who is regarded in such a high standard, but, in truth, is not living up to the standard that he preaches. It was those little bits and pieces that motivated all the characters coming in.

With Jeremiah, the young kid, I’ve always said that the story is more about him. It feels like he is almost an objective experiencer of the events. He has no real play in what happens. Everyone in the film repeatedly talks about how they consider him in their actions, how Helen will bring him up, and how Daniel has fallen short of taking care of him. But Helen’s and Daniel’s actions—and really the actions of everyone around him—prove to the contrary. They systematically seem to think without considering him, with a complete disregard for him, although they say the reverse. It says so much about generational trauma. So much of our future isn’t written by us, it’s written for us. That whole idea is fascinating and exemplified by Jeremiah.

The lone character we hear in standalone voiceover is that of Helen, the middle-aged matriarch played by Karen Kaia Livers. Her narration is heard throughout the film, so much so that the character comes to serve as something like the film’s conscience. What made you decide to position this character as the moral center of Burning Cane?

The story is told from Helen’s perspective, for sure. What’s redeeming about Helen is that she believes the entire time that what she is doing is right. She’s in the pursuit of what’s right, at least in her eyes. She’s grown in a prison of belief so she views everything through a harsh religious context. But because of that, her actions are dictated by that very, very strict fundamentalist interpretation of Protestantism that the rest of her community lives on. Helen, at the end of the day, is trying to do what’s right. She feels that what Daniel has done [by the end of the film] is so evil that she feels almost forced to put it into Biblical [terms] because of Tillman. What Tillman tells her to do is literally pulled from the Bible. He switches some of the words around to make it more action-oriented and make her more motivated, and then she then goes and acts. Although Helen is not infallible, she is definitely the one, amongst all of them, with the clearest conscience and the best intentions in what she does, even though she falls short of them at times.

Burning Cane is your first feature, but you’d directed a short before this.

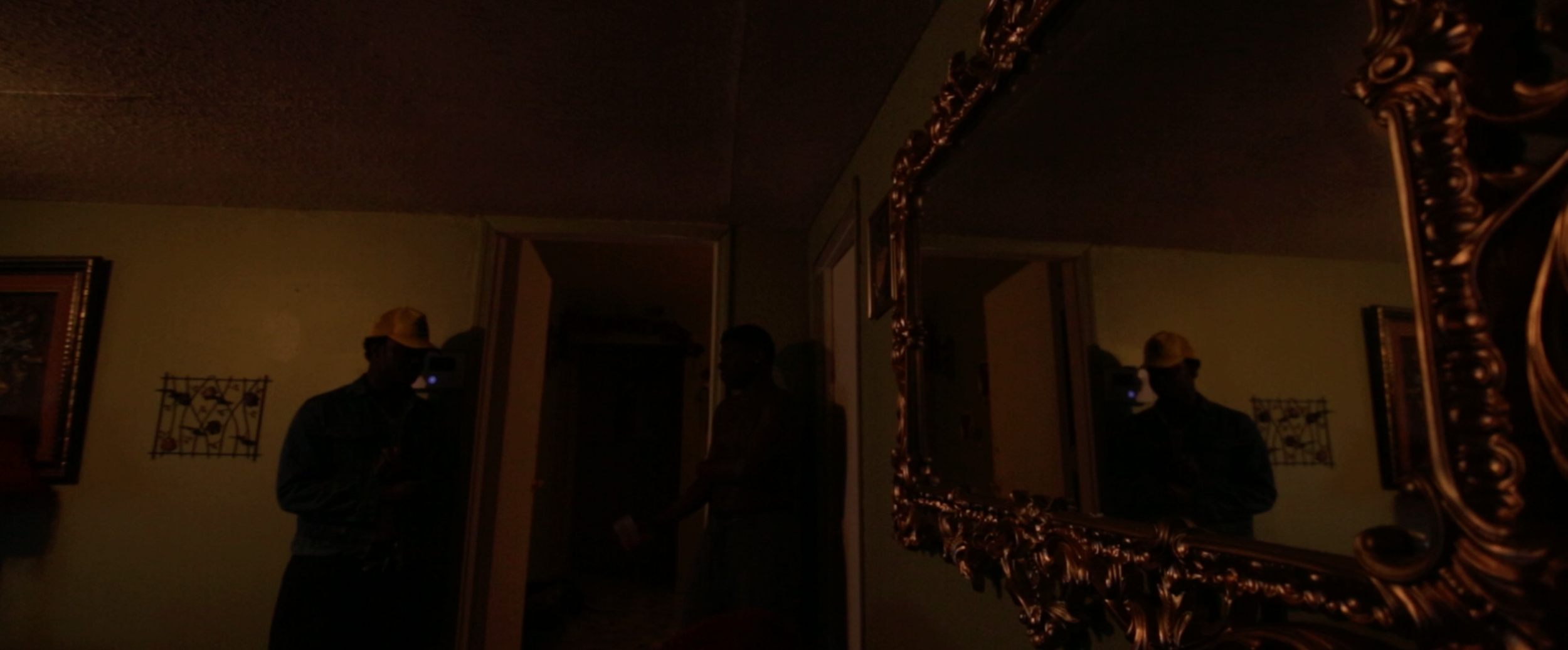

I directed this short called Ivory (pictured above) that I released at the Zeitgeist [Multi-Disciplinary Arts Center] in New Orleans. That was the first time I tried to do a theatrical [release]. This art-house theater agreed to play my short film for a week and if I could get people to come in and watch it, we would split ticket sales. Of course, there were only a few people who came in, but it was really cool to see that mechanism in action. And then, after that, I immediately went into making Burning Cane. Before that, I had made other shorts, but I never submitted or played them anywhere. I don’t know why that is. But before Ivory, I have fix, six, seven other shorts that I just made and were kind of sitting there, that I didn’t do anything with because I never felt satisfied with the end product.

I know why that is, it’s because I wasn’t putting in the necessary time and effort into making it the best that it could be. I was finishing shooting, whipping up an edit, but not really putting in the time to get feedback, not really making sure the audio was mastered—those kinds of things that really come into making a film polished and watchable even. I came to the realization that if I wanted to be good at this, if I actually wanted to do this as a career, then I needed to take it seriously, through and through. That realization came after I watched Ivory. I was talking it up so much to my friends, but, at the end of the day, I was not satisfied with it. I was a little embarrassed about that, and I told myself that I would never have that happen again. I want to be able to know that I put my all into everything, and with Ivory and those projects before, I cannot say that. But with Burning Cane and everything after that, I can.

I’m curious about how your preparation or approach changed on a larger-scale project like this.

It was a twofold thing because I was also shooting it. I wanted to be able to give my actors a little more space because on Ivory and every single project before that, I was very, very much over-their-shoulder, and in a way encroaching on that process. I wasn’t really respecting the creative weight behind my actors. And before [Burning Cane], most of my actors were my best friends, but still, [they] are artists and they have their own ideas. It felt like I was getting in my own way by not respecting them enough as artists. The projects always looked pretty cool, but I wasn’t getting the performances that I wanted, and I also wasn’t getting any of the feeling or mood that I wanted because I was overly dictating them and not letting the organic nature of the process take hold. In Burning Cane, I think I allowed for more of those mutualistic conversations than ever because I was forced to because I wasn’t as hands-on as I wanted to be because of the fact that I had to shoot and direct. That was a blessing in disguise because my actors had full strength. I could still come in and have those conversations with them, but I could not be over their shoulders, like I was before. That taught me a lot about respecting them and how important it is to come to set with a like-mind in terms of intention and character, but not to get bogged down by the specifics of their performances and be nit-picky about certain things and try to overly guide them to something else. Really, a director is a guardrail, but the actor drives the car of their character. That is what it is. And that realization was big for me.

Wendell Pierce is probably one of our greatest yet most underrated actors. How did he become involved with the project as both actor and producer, and what did he illuminate about the character of Reverend Tillman once you got on set?

Wendell is an amazing actor. He came on in a chance way. In the months leading up to production, I was raising money and working at a beignet stand called Morning Call Coffee Stand. And I was waiting on a woman named Lula Elzy and she asked me what I wanted to do with my life. I told her I was a filmmaker and I was making my first feature.

I walked her through all the characters, and at this point the pastor was the only role that hadn’t been cast. And then she asked me what I thought about Wendell Pierce playing the role. I think, initially, I was in a bit of disbelief. I didn’t believe it was possible. I was just like, [skeptical] "Okay," you know? But then she texted him right then, saying, Hey Wendell, there’s this NOCCA student who’s shooting his first feature this summer. He’s interested in you being in it. And then Wendell said, Okay, give him my email.

I got his email and I sent him the script. But after I sent it, I said, “Oh snap, don’t read it,” because the character of the pastor wasn’t expanded to the point that it needed to be. At that point in time, the pastor was more of a vessel for us to see the information that Helen is taking in from her church and reflecting in her everyday life. But when Wendell came on, the pastor [became] a much more pivotal piece of that revolving trio of [characters].

Wendell, without even trying, has an authority to him. He has a feeling of authority. His presence did so much to accentuate the mayoral status that pastors have. And also, Wendell opened up my mind up to the importance of allowing your actors to breathe life into their own lines. When I think about it, those sermons were like, “He who dies with the most toys wins, period.” They were rigidly articulated. But when Wendell came to set the first day, I went to his dressing room and saw his script pages. He asked me if I wanted them to be read that way and I said, “No, do what you want.” [I wanted him] to have the space to go off because that’s what Baptist pastors do in real life. They’ll start on the point of the sermon and then that can go anywhere. They might jump around the stage for five minutes. Being fluid, free, and organic in that way was important, and Wendell cemented that and did an amazing job. It was definitely validating to have an actor of his caliber take my work and my writing that seriously. It was flattering, to say the least.

Tillman is one of the vessels through which you reveal the hypocrisies and vulnerabilities of patriarchal figures within two of America’s most cherished institutions—the church and the family—in a way that is inextricable from the narrative events. How did you develop this potentially controversial commentary from Burning Cane’s conception into its finished form?

That commentary was all rooted in the questions that I had growing up and how I felt jaded by my experiences. I felt like so many of my questions weren’t answered. There were hypocrisies and fallacies that I recognized growing up in the church, and those never had concrete answers either. It felt like there was a conversation going on and we needed to talk about it as a people, as a community. I think moving towards secularism is, in our way, the right way. Religion and Christianity perpetuate a lot of antiquated beliefs and traditionalist values that we really have no place for nowadays—and there shouldn’t be [a place for them]. So I wanted to have that commentary and [have] people everywhere, but specifically my community of Black people to look at ourselves and that question.

I’m done telling people how they should believe, but I at least wanted to poke at the conversation. Even the conversation is a step in the right direction, to just actually look at it. If you unpack the history of us as Black people and Christianity, it’s a very, very interesting thing. We think about our conception of coming to the New World and America on slave ships—those African slaves were not practicing Christianity. It was a mechanism for control from the beginning… It’s true, we didn’t come here as Christians. We didn’t come here speaking English. All these sorts of things were a part of conforming to that Eurocentric society and mindset. There are so many layers as to why I think [that is] destructive. But in a modern context, the biggest thing was just wanting to comment on how [this] is slowly dying, especially amongst young people—that rigid, fundamentalist interpretation of Protestantism and religious zealotry in general.

In terms of moving that through the process, that was my substantive backing. But I want to say this: [when it comes to] seeing that [theme] used in Burning Cane, I did not want the piece to be defined by that. I did not want the film to feel like it was an overly judgmental, black-and-white thing. The film is filled with ambiguities because life is grey. I did not want it to feel in any way that it was a blistering exposé, you know what I mean? It’s a humanizing portrait. It was about these people. The commentary on religion was never supposed to be incredibly overt. When I talk about my intentions and the roots, where the story came from and what motivated me to it, [the religious angle] is where it leads. The story is about these people, this town, their hardships, their generational trauma, the continuation of vices and toxic masculinity—all of these things that I think exist within that rigid, religious ecosystem, but are not defined by that. I did not want the piece to be defined by that. If I’m judging these characters then I’m demonizing them right off the bat, and I did not want to do that.

Burning Cane helped me create a more nuanced understanding of my family and a lot of the religious figures and God-fearing people that I’ve known my whole life. Life is hard and sometimes people need an emotional refuge… there’s no reason that I should be the one telling telling them that they shouldn’t have that, regardless of how I feel. I can only speak my truth. I cannot continue to tell people what I think they should believe because that only ends in arguments and never leads to the result that you want.

You are among a rare breed of filmmakers who has worked as director and cinematographer on your films—in addition to writing and editing Burning Cane. What obstacles did you confront in lighting, framing, and creating the visual language of the film while attending to your multitude of tasks as director? How did you overcome them?

The biggest challenge of shooting and directing came from the mind-split and not necessarily being able to be as present as I may have wanted to be. But my intention in shooting it was to create a documentarian, fly-on-the-wall style that was [achieved through] shoulder-rig, handheld [cameras], just very active and kinetic camerawork.

I wanted to go with natural and practical lighting setups, which I felt could exist in a world where anything [is] pre-lit or preplanned. That worked from an aesthetic standpoint, but it also worked for the resources that we had, if I’m being completely transparent. It was a marriage of style and circumstance. That is the way I like to shoot even now with the short that I’m about to make for Hulu in the next couple of days. I’m shooting it on film with all-natural, organic lighting, which I love to use. But during Burning Cane, it just helped to shoot that way.

Where were you when you found out that Burning Cane got into Tribeca and what was that experience like?

It was out-of-body. I thought that [Burning Cane] would go [to a festival], I thought it would work out, but you really never know. I felt like I put my all into Burning Cane and I felt like there was a chance we could get into one of those major festivals. But [then] I got an email from [Tribeca Festival Director] Cara Cusumano, saying that she thought it was a beautiful film and that she wanted to speak to me and Wendell. Wendell was out of town so then I went to meet with Cara and talked to her about the festival. That’s the day when I first found my managers through Benh Zeitlin [the film's executive producer] and his team at Untitled Entertainment… It was a dream circumstance, having the film shown, having it seen, especially since you don’t know if it’s ever really going to be seen. It was validating, like some of those other steps along the way, but it was surreal in that I hoped it would happen, but never thought it would. The fact that it did happen has literally changed everything about the trajectory of my career as an artist.

What was it like to see your film not only premiere at Tribeca but then also sweep the awards ceremony?

Before the premiere, I was horrified. I had a knot in my stomach. My dorm at NYU was Third North, which was right around the corner from Village East Cinemas, [where the film premiered]. I was with my friends and we were all gonna go to the premiere and I was so fricking nervous. And then all my family was there and a lot of them at that point weren’t quite aware of how the film shows God-fearing people in a fallible light. So I was a little nervous about how they would feel about it. But they’re still proud of me based on my work ethic and my devotion to my artistry in general, though they don’t always agree with the things that I say and think. At the end of the day, they do respect that I am my own person. And I saw that really first-hand after the screening, which wasn’t as bad as I feared. It was one of the first times where I was speaking openly about speaking differently, and it didn’t seem to change anything. We still had a happy [celebration]. We went to the pizza place across the street from Village East after the screening and the mood was high. Really, no one was talking about those kinds of things. And that meant a lot. For the first time [in my life], it wasn’t an objective taboo to think differently.

I would also say that I was just nervous in general. Sitting through that screening was grueling, I have to be honest. I don’t sit through any screenings after that because I get so neurotic about everything that everyone is doing [during] the film. When someone goes to the bathroom, I get offended. You know what I mean? And people have to go to the bathroom. Sometimes people like faster-paced work, and that’s okay. Everyone’s not gonna like the piece. I have a more nuanced understanding of that now that I didn’t have back then.

In terms of the awards ceremony, that was also completely surreal. Tribeca as a whole was surreal. Jane [Rosenthal] invited me to this brunch at her place, and that was the first time I met Leonardo DiCaprio, [Martin] Scorsese, and Robert De Niro, people that I had dreamed but never thought I would see in person, let alone talk to and have them be interested in my work as a filmmaker. That was surreal, man… Tribeca was maybe the most joyous… I don’t know, I just look at it with such rosy eyes. I love, I love, I love Tribeca. I love what it meant, I love what it means. It changed everything about my life.

How did the film then find its way to Ava DuVernay and ultimately secure distribution with her arts and advocacy collective ARRAY?

After the film was at the Festival in May, we waited a couple of months. There were distributors who had liked and were interested in the project and we were in talks with some of them. But ARRAY seemed to be the one that was most interested. And I did some more research on ARRAY, saw that really all of their works were by filmmakers of color and women. And I thought that was tight. I wrote an email out to Ava, who founded ARRAY, and Tilane [Jones], who is ARRAY’s president, and outlined my process, how Burning Cane was made in a very grassroots way, how it’s a story that’s uniquely Black. Burning Cane is a bleak cautionary tale, but it’s still about humanizing the Black experience. I wrote that down and I felt that their intentions as artists and filmmakers were the same as mine.

After that, I got a call from Ava. And that was insane. I was at Bobst Library near Washington Square Park, and I got a call from a number [I didn’t recognize]. I picked up and she said, “Hi Phillip, this is Ava DuVernay.” I freaked out and was like, “Hold up, I’m in a library, let me call you back.” I ran outside the library, called her back, talked to her about my intentions for the distribution. She asked what conversation I wanted to start, and I told her that I wanted to, in truth, open up a wider community conversation about the rigid reputation of Protestantism and have Black people take an objective look at religion and its role in our lives. And I wanted us to broaden that conversation, I wanted to visit HBCUs. Ava made that happen. I had an amazing screening at Spelman. I went to the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian and had an incredibly stimulating conversation there after the screening. It was a grassroots distribution and it was perfect for such a grassroots film. So shout-out to ARRAY and all the dope Black women who run that company. I’m just grateful that they took in the film and embraced it.

You’ve now worked with some of the industry’s most acclaimed luminaries, veterans, and directors, from Ava DuVernay (pictured below) to Wendell Pierce to Benh Zeitlin. What have you learned from them and applied to your own process?

There are bits and pieces that I’ve taken from all three of them. One specific lesson from Wendell is to always remain a student of your craft. You can never stop learning, you can never stop learning more. Wendell is definitely one of the most vocal advocates for me to stay in school. He feels that no matter how talented I am, it will only make me better to continue to learn more. Although I feel I learn more in the field and in actual, physical production scenarios, the sentiment of what he is saying is right: never be too rigid to learn new things, always be a student, always be open to new things. The moment your perspective becomes rock-solid then you cease to grow.

Benh only works on projects that Benh wants to do, and that’s what I got from Benh: to be honest about my intentions and voice as an artist and to only go after the projects that I can truthfully say that I’m motivated to do and that I feel a personal connection towards. With that, every question is answered. I just found it so dope that Benh [is] such an auteur in a rigid way by exclusively working on stuff that he wants to work on, his projects. He’s not a director-for-hire. I recognize that that’s what I want: in terms of the feature space, I want to only work on the projects that I personally wrote and directed.

I learned from Ava—and the marketing phase of Burning Cane—to understand when it’s time to take a step back and let people do their job. I was being so neurotic about the marketing materials because I was so attached to them from beginning to end because I had really done everything else on the project, in terms of accumulating those creative materials. By that time, I was honestly getting in my own way. And I asked [Ava] questions and she was very honest with me. What I took away from her answers was that it’s okay to take a step back, take a chill pill, take a breather, and let people do their jobs because something beautiful can happen from it, and something did. The poster that ARRAY made was so dope and nothing that I could have imagined. That came from allowing the people who do this for a living to do their jobs.

You’ve revealed that your next narrative feature, Magnolia Bloom, will center on the Black Panthers in 1970s New Orleans, and I saw that the project was recently accepted into the Sundance Screenwriters Lab so congratulations on that! What light do you hope to shed on these oft-misunderstood activists and community organizers through your filmmaking?

Magnolia Bloom is about creating a humanizing portrait of those New Orleans Panthers. They were kids who were 13 to 22-years-old and [were] operating within a very, very hostile, de facto Jim Crow environment. That being said, they were driven forward in parallel with their community by the love they had for each other. The film is about communal Black love to the highest degree. It’s about people that you may not be blood brothers and sisters with, but for whom you would take a bullet. Those bonds are real and beautiful and thicker than blood.

As someone just emerging in the industry and still discovering and shaping your identity as a filmmaker, what do you want to see more of in movies on the whole?

Of course, we need to be more inclusive and open up the spectrum of stories and make sure that stories are told from an authentic perspective. I think it’s important, even as new filmmakers coming in, that we try to tell stories that we honestly feel we can give authentic insight on because that always makes for the most honest, nuanced storytelling. And I also think that you have to be the change you want to see—or you have to be the vessel of the art you want to see and want to make. My duty now as a filmmaker is to make sure that I am only providing a humanizing lens on the Black experience. I feel a very big responsibility to make sure that I am giving an honest and humanizing portrait to Black people, my community, of our experiences because they are nuanced and they have not always been portrayed as such. It is a responsibility, but it’s a responsibility that I feel honored to have.