BY MATTHEW ENG |

SHOW ME A HERO’s Oscar Isaac is the Real Best Actor of 2015

This year's best performance by a lead actor can’t be found in theaters.

It has been said countless times this awards season but it deserves to be said again: it is, indeed, a shockingly dull year for Best Actor.

Which isn't to say that there haven't been plenty of impressive performances from leading men at the movies. But the trouble is that they tend to appear in deserving films that are hard to imagine Oscar voters embracing, like Victoria's poignantly vigilant Frederick Lau, The End of the Tour's rivetingly responsive duet between Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg, Macbeth's blazingly worthy Michael Fassbender, or Straight Outta Compton's marvelous trifecta of Corey Hawkins, O'Shea Jackson Jr., and Jason Mitchell. On a few occasions this year, great performances have been given in films that are on Oscar's radar for every category but Best Actor, like 45 Years' devastating Tom Courtenay, Son of Saul's indelible Géza Röhrig, and Love & Mercy’s eloquently-addled John Cusack and Paul Dano.

Every single one of these actors has achieved performances that should be continued topics of conversation among the Academy. But none of them have cut even nearly as deep as Oscar Isaac in Show Me a Hero, which is a wondrous and walloping characterization that ranks among the very finest performances in contemporary film…except that it aired on television.

HBO's miniseries Show Me a Hero recounts a gripping episode of real-life communal schism, in which government-mandated efforts to build affordable public housing in 1980s Yonkers were met with resistance by the neighborhood’s predominantly white, middle-class residents. Equal parts historical docudrama, institutional survey, and Shakespearean tragedy, Show Me a Hero features one of the year's absolute best ensembles, crammed with easily-recognizable veteran character actors (like Bob Balaban, LaTanya Richardson Jackson, Catherine Keener, Alfred Molina, and Winona Ryder) and plenty of fresh newcomers of color whom I can hardly wait to see more from (including but not limited to Dominique Fishback, Ilfenesh Hadera, Natalie Paul, and Carla Quevedo). Each and every performer imbues his/her role with a rich and humbling streak of humanity that settles this story in a world that is so easy to recognize because it is so clearly our own. There's not a bad performance in the bunch, a feat that belongs just as much to David Simon (who molded great characters from such resonant source material) and Paul Haggis (who directed all six episodes of Hero with surprising and sobering attention to detail) as it does to the engaging actors who approached these roles with an authentically lived-in understatement that tempers the series’ most volatile moments.

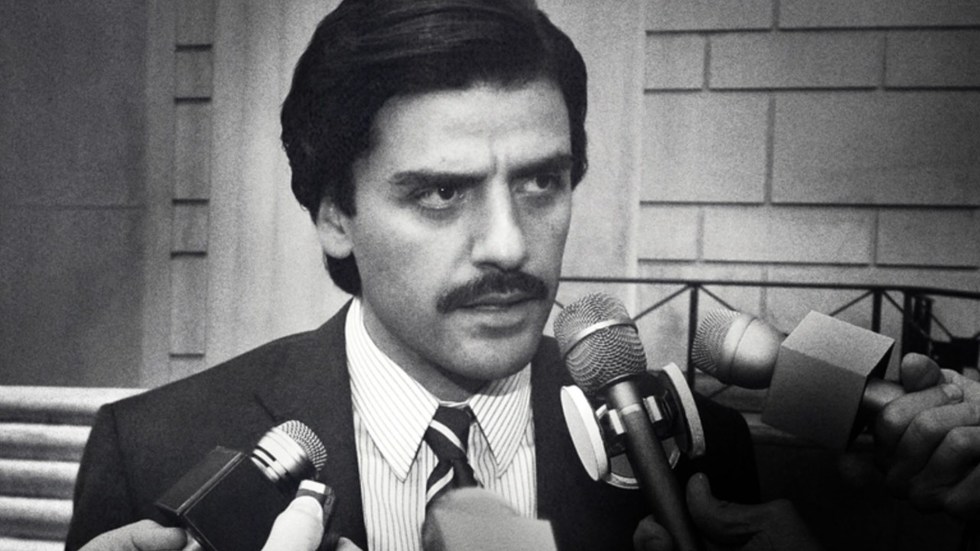

At the epicenter of the storm is Oscar Isaac, who over the course of Hero's six exhilarating episodes solidified himself once and for all as the most fascinating actor of his generation. Isaac stars as Nick Wasicsko, a former police officer-turned-local councilman who becomes mayor of Yonkers (as well as America’s youngest big-city mayor) in 1987, only to find both his mayoral residency and political rise curtailed when his pro-housing stance drew the extreme ire of his city’s most vocal dissenters and drove away his most loyal loved ones and professional allies before meeting a tragic end.

In truth, we've seen this character arc plenty of times before. In many ways, dramatic storytelling was built upon the downfall of monomaniacal men in power. But what sets Isaac’s performance apart—actually, what makes his work in Hero a landmark interpretation of this archetype—is that he never actually plays the hero.

In Isaac's skin, Nick Wasicsko is indeed an ambitious, committed, and charismatic political venturer, a proud and poised hometown boy done good. But there's always a trace of unnerving desperation, a distinctive sense of unease that's gradually chipping away at his confident surface from as early as the first episode. As Nick's fall from grace only grows steeper, Isaac strips away layer upon layer of Nick's outward cool, revealing a much more profound portrait of a man trying and failing to cover his torment and keep a level head. Much of this is due to Isaac’s skillful physical embodiment, which traces a character arc all on its own, from early, cock-of-the-walk pride to fidgety, slump-shouldered shame. But his power exists on an almost psychic plane as well.

In short, this series needs Isaac, who has a preternatural yet underutilized ability to feel his characters' inner anguish and then make us feel it through some sort of invisibly electric connective tissue between actor and audience. Isaac can take a question as potentially and impossibly treacly as "If I'm not the mayor of Yonkers, will you still love me?" and turn it into the most heartbreaking line reading of the year by simply saying it with uncommonly abundant sincerity. But he can also enact an explosive bureaucratic screaming match and stir up our own outrage through the sheer conviction of his playing or dweebishly flirt with Quevedo (lovely as his wife, Nay) and Ryder (eternally alluring as his crush/colleague, Vinni) and instill in us a weird sense of giddy friskiness through his own unconventional charm, as though we’re experiencing the rush of these moments through Isaac, who suddenly emerges in Hero as a fantastically full-bodied vessel for all of life's complex emotions.

This gift of Isaac's—honed at Julliard, but unteachable otherwise—has been largely withheld from us on the big screen, which isn't a demerit so much as a necessary adjustment to specific projects, tones, and characters, whether it be Inside Llewyn Davis’ mournful yet distant titular folk singer or A Most Violent Year's equable entrepreneur, both expert performances that are largely internalized, with only fleeting moments of conspicuous emoting behind those handsomely joyless facades. Here, however, Isaac is at last unburdened from having to keep a tight lid on his emotions and releases them with the assurance and vitality that is visible in all of his work, but never more so than in Hero. In the series' single most wrenching image, we watch Isaac as Nick, alone and in confined close-up, as he undergoes a panic attack. He attempts to call out to his brother, but he can only eke out a pitifully ashamed whisper, choking on his words amid a stream of tears. It's an enormously moving piece of acting, not so much a cathartic release as a necessary progression of despairing emotions, a regretful step into further, unavoidable darkness that could have only been achieved by a performer who has laid such unpredictably riveting groundwork in every single scene leading up to this.

In an industry overcrowded with young actors who seem intent on becoming Harrison Ford and Arnold Schwarzenegger surrogates, Isaac is the rare performer who would seem pleased to be called a "character actor." I can easily imagine him existing and thriving in an earlier decade of entertainment, which makes sense since his particular acting style continually conjures up the vivid ghost of peak-era Al Pacino, who was, and occasionally still is, a peerless embodier of seemingly nameless forms of unshakeable angst. Like Pacino, Isaac can showboat with the very best of them, as his rug-cutting, film-stealing performance in Ex Machina so recently proved. But we accept the forceful and flamboyant moments, even in the quieter turns, because they so clearly derive from a well of inarticulate sorrow and self-loathing, a kind of pain that seems to emanate from the pores. Pacino incarnated this with that famously simmering brood of his, which Isaac emulated to magnetic effect in A Most Violent Year, but the latter actor's emotional vocabulary already feels full of even more pieces that comprise an even sturdier whole than his most obvious acting ancestor.

Between Show Me a Hero, Ex Machina, the 2015 Tribeca selection Mojave, and that underdog little indie Star Wars, Episode VII: The Force Awakens, it has been a banner year for Isaac. I'd hand him six Oscars and at least as many Emmys on the sole basis of Show Me a Hero, an illuminating, involving, and ever-timely chronicle that I cannot possibly encourage more people to take a chance on, if only to experience an essential performance from an actor whose work we'll certainly be talking about for decades to come.

I'm sure that Isaac's relatively recent rise will offer up even more prestigious projects and beefy roles that will keep him firmly planted on our movie screens. There’s a strong likelihood that Show Me a Hero might be relegated to little more than a fond, easy-to-overlook footnote by the tail-end of Isaac's hopefully legendary acting career. The series itself impressed critics but didn’t necessarily set cable audiences ablaze, so there’s a high chance that it already might be. And that's a shame.

For those who have screened Show Me a Hero and witnessed Isaac's incomparable star turn (which, ironically, is free of any of the vanity or self-awareness that the term "star turn" usually implies), it's impossible to imagine Isaac’s Nick Wasicsko existing anywhere but the front of our minds. Few characters become so permanent and so real a fixture in your memory that you swear you've directly interacted with them at least once in the not-so-distant past. By resisting high drama for the sake of heroically humane inhabitation, Oscar Isaac has instead offered us what is unmistakably the stuff of life.