BY MATTHEW ENG |

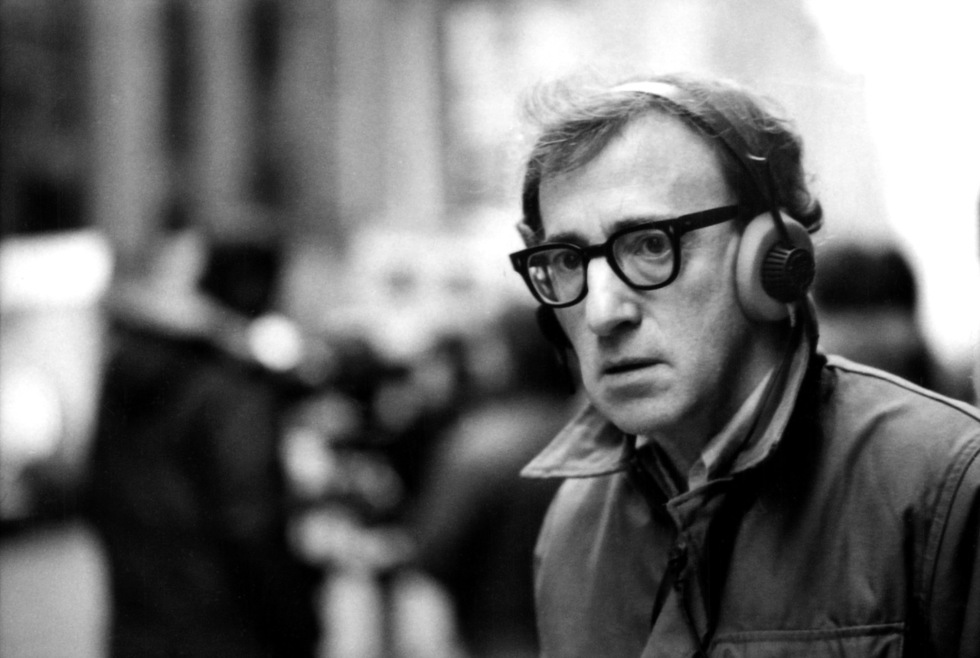

An Auteur Comes Out of His Shell — Slightly: Is Woody Allen More Public Than Ever Now?

Amid the release of his latest film, a more accessible, personal, but just as nervous Woody Allen emerges.

Woody Allen has always been reserved but he isn't a recluse.

Allen has never entirely shied away from press coverage, and still allows his films to make high-profile debuts at premiere international festivals like Cannes. Barbara Kopple entertainingly cracked open the Allen myth in her 1997 documentary Wild Man Blues, which followed Allen's European jazz tour in the years directly following the Mia Farrow/Soon-Yi Previn debacle, although it's more of a momentary portrait than a definitive Allen chronicle. Allen's still an active jazz musician and it's still easy enough to spot him strolling along the Upper East Side with wife Previn. Last year, he made a rare foray outside of his own filmmaking bubble by starring in John Turturro's negligible erotic comedy Fading Gigolo, about an unconventional male escort (Turturro) and his unlikely pimp (Allen). Allen still wins Oscars. He still works with movie stars. And for the past thirty-three years, he's written and directed a film a year, without fail, and these films continue to make sizable receipts, even if the type of luster that once universally attached itself to Allen in the days of Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters only continues to pale, a shift in reception that continues to be frequently dissected itself. Allen's later output has been either depressingly perfunctory or pleasantly time-killing, with not a single work cutting even half as deep as his pre-nineties masterworks.

So, why then, does it suddenly feel like Allen is more visible than ever these days?

The actual number of appearances and interviews Allen has done for his latest scabrous black comedy Irrational Man, which opened in mid-July, isn't exceedingly higher than the usual number Allen puts in for any of his movies, even when silent invisibility might have seemed like a more fitting option for recent critical bellyflops like To Rome with Love and last year's Magic in the Moonlight. Rather, it's the interviews themselves that have become increasingly attention-grabbing, whether by Allen's intention or not, but also oddly — and at times joltingly —candid. The most noteworthy is last week's wide-ranging NPR interview entitled "At 79, Woody Allen Says There's Still Time To Do His Best Work," a misleadingly optimistic title for what is essentially one of the gloomiest interviews Allen has ever given. The heavily-covered comments Allen makes about Previn's "youth and energy" and the controversial couple's "paternal" relationship are stomach-turning in their dubiousness. But what really fascinates about that piece is just how willing Allen is to not only detract from his own lopsided oeuvre and lenient filmmaking methods — which he's always done — but to actually define himself as both artist and human being in a way that's bluntly honest and almost carelessly transparent in its humility and pessimism.

"I'm lazy and an imperfectionist [sic]," Allen says in the NPR article. "...I don't have the intellect or the depth or the natural gift. The greatness is not in me." That statement shouldn't necessarily come as a surprise to anyone who has sat through Whatever Works, but from the mastermind behind Annie and Hannah — as well as Manhattan, The Purple Rose of Cairo, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Bullets over Broadway, not to mention undersung treasures like Another Woman and Husbands and Wives — that's a different and distorted statement entirely. It still feels unusual for one of America's most prolific and revered auteurs to rebuke his own repute with such defeated, hands-in-the-air resignation, like some sort of modest canonization in reverse. When Allen is called out on his doom-and-gloom demeanor by NPR interviewer Sam Fragoso, he retracts, but only marginally: "All I can do is try to do good work so that people can say, 'In his later years, in his last years, he did some of his best work.'" It reads like an artist closing the casket on his own career, except that this artist happens to have a forthcoming film with Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, and Bruce Willis already in pre-production and a planned six-episode TV series that he's writing and directing for Amazon.

From Annie Hall's rueful look at the pleasurable-painful inevitability of love and couplehood to Husbands and Wives' cyanide valentine to the same exact theme, Allen's films often tend to reflect their creator's life; Annie was made at the tail end of his relationship with Diane Keaton and Husbands finished filming only days after the Allen-Farrow partnership bitterly unraveled. Much more often, however, Allen's films — the best of them, that is — are reflective, sensitive distillations of his own neurotic impulses that cast Allen in a clearer light than his own off-screen self-analyses, which often touch on his penchant for angst and over-anxiousness with a lightness that is just as verbally dexterous as it is emotionally disarming. Even the lightest of Allen's comedies are shaped by a characteristic sense of existential dread, but Allen's recent statements aren't cloaking these fears with well-placed wit or waggishness. There's a wholly unfunny brusqueness to his declaration in the NPR piece that, "You and I could be standing over [William] Shakespeare's grave, singing his praises, and it doesn't mean a thing. You're extinct." Or: "It wouldn't matter to me, aside from the royalties to my kids, if they took all my films and dumped them." Gone is the broadly-pitched cleverness of a classic Allen standby like "I am not afraid of death, I just don't want to be there when it happens," or "I don't believe in the after life, although I am bringing a change of underwear."

Why is Allen going so deep and getting so bleakly and unflinchingly real at this particular point in his career? But, more to the point, why is he doing all this for Irrational Man, another post-post-Mia undertaking that seems destined to join Melinda and Melinda and Cassandra's Dream among the ranks of seemingly innocuous Allen films that are neither great nor awful, but are still seldom talked about? By my measure, Irrational Man is actually one of the more successful Allen enterprises of the past twenty years, even if it once again fails to touch even the shoulders of a tonally and thematically similar predecessor like the superb Crimes and Misdemeanors. Irrational Man boasts the most engagingly lucid performance of Emma Stone's young career, one of Allen's better-integrated and more believable acting ensembles in years, and a genuinely engrossing comic-romantic-suspenseful story, in which Joaquin Phoenix's drunk, despondent, impotent philosophy professor contemplates the perfect murder of a crooked judge. The film is funny, involving, and finely-performed, but there's also something inherently disturbing at its core, an unshakable ugliness to the central, age-inappropriate romance between Phoenix and Stone, as the former's worshipful pupil turned obsessive companion turned passionate paramour. Irrational Man's most provocative narrative twists and its startlingly conclusive message all revolve around the harmful and downright menacing influence that powerful men exert over impressionable young women, which feels like an unpleasant coincidence that might not have even pronounced itself so explicitly were it not for former stepdaughter Dylan Farrow and the troubling sexual abuse allegations that resurfaced in the form of her harrowing open letter, which The New York Times published in February 2014 during the time of Blue Jasmine's awards-run.

Personally, I stand with Dylan Farrow. But this isn't a piece about trying Allen, who continues to vehemently deny these allegations, even though Farrow's aren't the only claims of questionable behavior. I don't think Allen's sudden string of straight talk is an attempt to detract from what may be, at best, disagreeable, and, at worst, triggering in Irrational Man's gradually degenerating romantic conceit. Nor does the film feel like a knowing response to the harshest critics of Allen's professional and alleged personal lives, although surely even Allen might have noticed the unusual timing of this specific endeavor, even if the strangely uncanny self-portraiture was initially an unwitting coincidence. The film, while lifting Allen, however briefly, out of his self-led artistic rut, remains uncomfortable meta-cinema for anyone who has the younger Farrow on the brain, but there's another, comparably stark story at the forefront of the film, this one about a man of once irrefutable glory who decides that the only way to reclaim his vitality and reverse his fate is by taking quick and decisive action, no matter the risks or moral consequences. Indeed, numerous montages in Irrational Man show us Phoenix's collegiate sad sack looking downright rejuvenated and ready to embrace life by the mere possibility of taking a new course of admittedly lethal action. We see Phoenix gorging on greasy diner meals, engaging excitedly in his teachings, and shtupping Parker Posey's willing and desirous colleague, all while crafting a cold-blooded murder with a clear head and creativity. For a long while, any and everything seem possible.

Allen is a storyteller inextricably linked to his male protagonists and the innermost thoughts, guilts, and insecurities that fuel their onscreen actions. This bond between character and creator goes a long way in explaining why I can't help but see a certain slice of Phoenix's disillusioned, self-aware academic in this suddenly more venturesome Allen, who is currently embracing a medium he hasn't dabbled in for decades (even if he already regrets the decision), getting in front of the camera for both his own projects and others', and speaking publicly and truthfully about his own self-perceived shortcomings as a filmmaker during a period in which many of our oldest masters would start putting together their valedictory efforts and receding from the spotlight, save for the occasional and inevitable AFI or Cecil B. DeMille Lifetime Achievement Awards. Allen's obviously thinking bigger picture and if that NPR interview confirms anything it's that stopping or slowing down just isn't an option, even if it's more out of tried-and-true routine than actual inspiration.

I don't know if we'll ever see a full return to form from Allen, but it's clearer, now more than ever, that he'll keep on working at it well into the twilight of his career. Even after forty-four films and over sixty years in the industry, Woody Allen still seeks our approval. He cares, in spite of himself.