BY MATT BARONE |

Anthony Bourdain Helped Tribeca 2016 Honor an Overlooked Icon With JEREMIAH TOWER: THE LAST MAGNIFICENT

Back in 1970s, Jeremiah Tower revolutionized the chef business, yet many people still don't know his name. Yesterday, at the Tribeca Film Festival, though, a new documentary premiered that should help fix that.

"We should know who changed the world—we should know their names."

That's just one of Anthony Bourdain's many quotables about the game-changing, controversial, yet largely under-valued chef Jeremiah Tower, who's the subject of the new CNN Films documentary Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent, which was just picked up for distribution by The Orchard. Revolutionary for the "New American Cuisine" movement in the 1970s all the way into the late '90s, Tower has never truly received the credit he deserves, due to a few burnt bridges and an extended period of self-exile that turned his narrative into more a question mark than an exclamation point.

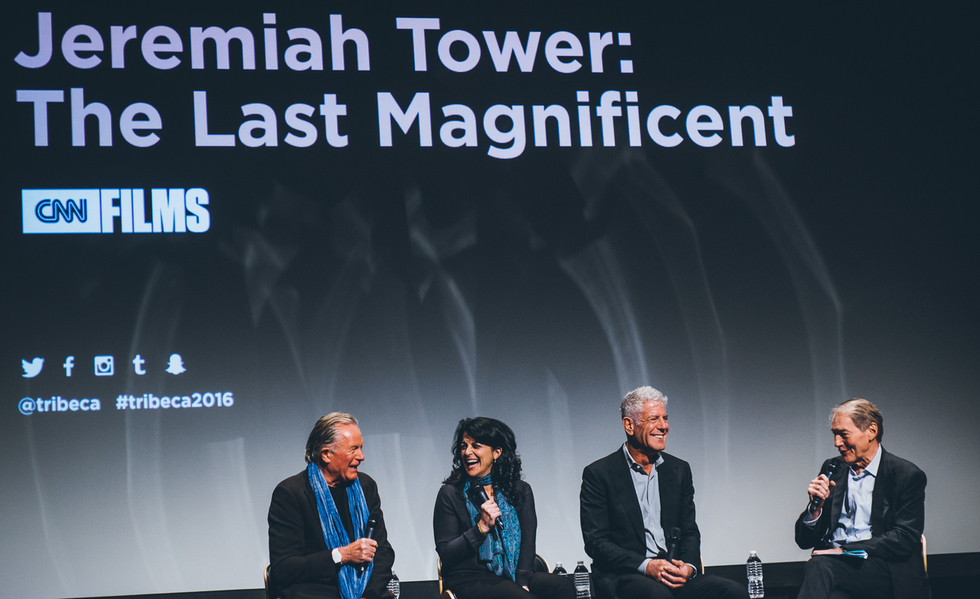

Yesterday, at the John Zuccotti Theater @ BMCC, the film, beautifully directed by Lydia Tenaglia, had its world premiere as part of Tribeca 2016's Tribeca Talks: After the Movie series, with a post-screening conversation between Tower, Bourdain (who also produced the film), Tenaglia, and guest moderator Charlie Rose.

With talking-head insight from celebrity chef Mario Batali and multiple other food industry luminaries, The Last Magnificent dutifully makes its case on why Tower, as Bourdain puts, "changed the world," but Tenaglia's film's most commanding voice is that of Tower himself. Through a tightly edited mix of original interviews, archival footage, and gorgeously shot recreations of Tower's younger days, which look like saturated old home videos come to life, Tenaglia peers deeply into the psyche of an endlessly fascinating and bluntly honest man. "We didn’t want it to be a fluff piece," Tenaglia told Rose. "We wanted to go deeper than that."

As a kid, Tower was raised by his "prick" of a father and his "alcoholic" mother, who both live affluently and provided their son with an almost Great Gatsby-like upbringing. While they were off rubbing elbows with high society’s elite, Tower would be left alone on massive ocean liners and in fancy hotels, and it’s in those lofty places where he first fell in love with high-end cuisine. The Last Magnificent charts the openly gay and, as Batali describes him, "glamour-puss" Tower's course from that lonely yet liberated childhood experience through his professional breakthrough as the head chef for the Bay Area's infamous French-themed restaurant Chez Panisse, his starry-eyed 1980s days running San Francisco’s lavish Stars, his mysteriously off-the-grid time following Stars' closure in 1999, and his recent controversial stint as Manhattan’s Tavern on the Green's head chef.

Tower’s efforts at Chez Panisse and Stars are The Last Magnificent's anchor. Tower, Tenaglia, and her interviewees break down just how the iconoclastic cooker singlehandedly elevated his profession; before Tower, there were no celebrity chefs, and American cuisine didn’t have a personality. But with his larger-than-life personality, magnetic charisma, and proclivity towards open kitchens and masterfully worded menus, Tower is as important to his industry as, say, Rakim is to hip-hop and Chuck Berry is to rock 'n roll. As restaurant consultant Clark Wolf puts it in the film, "Before [Tower], if you were a chef, your mom didn’t tell anybody."

Like many creative geniuses, though, he’s also an enigma whose reputation precedes yet also fails to demystify him. "There's a locked room, a private room inside Jeremiah Tower," says Bourdain in The Last Magnificent. "I haven't been there. I’m not sure many people have."

Thanks to Tenaglia’s film, however, the world will finally know the real man, and, if justice is served, universally acknowledge his importance. The first steps towards honoring Tower’s unfairly overlooked greatness were taken during yesterday's panel, a lively and celebratory discussion centered around the film’s subject. Bourdain told Rose about why it was so crucial for he and Tenaglia to tell Tower’s story after reading his memoir, California Dish, and feeling a sense of "historic injustice." "It became a cause for me," said Bourdain, "to tell a story in an almost evangelical way about how large a figure he is. The menus, the restaurants, and the food we eat are all Jeremiah. And I don't think he's gotten his due."

Bourdain later added, in regards to how Tower was almost written out of the food industry's history books, "When Jeremiah left San Francisco, the history of American cuisine was left for the victors to tell… It was easier [for them] to tell a simpler story," one that didn't cite Tower as their biggest influence because he’d angered many of them.

One of the talk's more entertaining stretches was dedicated Tower's brief stint at Tavern on the Green, a move that shocked the foodie community when an unexpected New York Times tweet announced Tower's latest gig in November 2014, a time when many didn’t even know where the man had been for several years. On his decision to take over the credibility-challenged New York City establishment, Tower quipped that he has a "fatal attraction for the slim chance." Bourdain, though, described the bizarre move with the event’s funniest quote: "Jeremiah is about fabulousness. That's not Tavern on the Green—that’s where you bring your grandmother because you know you won't see your friends there."

Near the end of the conversation, Rose asked the panel if Tower's unique blend of radical individualism and professional excellence can be taught to others or if its birth-given. Bourdain circled back to Tower's uncommon youth spent on ocean liners and five-star hotels being pampered by staff and doing nothing but eating. "It's no accident that so many of the great chefs, the great innovators, they were lost children," said Bourdain. "They were people for whom childhood was not ordinary."

Tower's excellently on-brand response told the crowd everything they needed to know about him: “I can tell you that no one in this theater wouldn't want their feet tucked into bed by a handsome steward who feeds you a nice dish of consommé.'