BY ANDREI SEVERNY |

Why We Must Free Film From Running Time Prejudice

With the rise of more time flexible distribution platforms, it's time for cinema to break free from the old established running time restrictions.

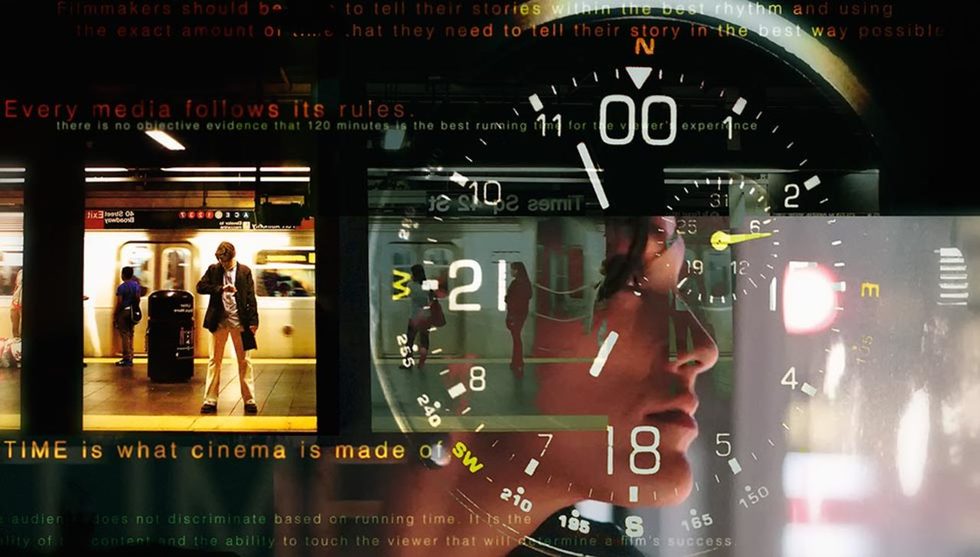

Time is what cinema is made of. This art form stands out among the rest because of its intrinsic nature that lies in the visual flow of recorded time. In his book Sculpting in Time (1986), Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky noted how time is the main organizing force in cinema, “The dominant, all-powerful factor of the film image is rhythm, expressing the course of time within the frame.” Tarkovsky was the master of long shots of true cinematic magnetism, which absorb and elevate the viewer from everyday life and carry unparalleled spiritual depth.

Freedom and restrictions in literature and cinema

We live in a time when limitations on content are fashionable. Shorter forms of content often tend to be shallow, encouraging the viewer to jump to the next item without much thought. Back in 1992, Roger Ebert wrote, “Why is it nobody seems to realize how lots of short little things are exhausting? You have to keep setting your mind back to zero. But the long, deep stuff – the long books, the long movies, and even the TV miniseries – are refreshing, because they give you the time to understand other lives and even, for a time, seem to share them.”

Every media follows its rules. Twitter limits each entry to 140 characters. Focused and informative newspapers adhere to article word count of around 800. But the highest form of literature – a book – enjoys total freedom of length. It is the content that matters.

Similarly, popular apps – such as Vine and Instagram – limit videos to a few seconds. Television is constrained by a rigid schedule grid to allow time for news and advertising. Why isn't the art of film allowed the freedom from length limitations that we so freely grant to books?

Quest to find an audience

As an independent filmmaker your job is not only to conceive and give birth to your film, but to send it off to meet its audience. Even if you gave up the ambition to show your film theatrically and just want to put it online, major platforms like Netflix, iTunes and Hulu would most likely not talk to you. You could proudly put your film on your own website, but no one beyond a fraction of your Facebook and Twitter friends would even know it's there.

There is no objective evidence that 120 minutes is the best running time for the viewer’s experience.

You could then try the traditional route. When submitting your film to festivals, you'll notice that films are segmented into categories not only by genre, but also by running time. The most desirable and prestigious is a feature length film defined by different organizations as films longer than 40 or 60 or 70 or 80 or 90 minutes.

While there are many competitions and venues for short films, the running time ranges between 20 and 70 minutes and anything longer than 160 minutes is less likely to get accepted.

The 120 minute trap of the existing distribution models

Even if your creation gets this far in the selection process, the next deadly challenge is to find a distributor. The unwritten rule for feature films is to make it as close to 120 minutes as possible. Even established filmmakers give in to the pressure.

Let us not be deceived – there is no objective evidence that 120 minutes is the best running time for the viewer’s experience. The reason is an old theatrical marketing habit, a compromise between the audience getting their money’s worth and maximizing the number of screenings per day.

The myth of the shortening attention span

For decades people have been talking about the changing appetites of viewers towards videos of cute cats and flipping channels in search of the next wacko experience. Kevin Spacey brilliantly challenged this notion in his recent speech at the Edinburgh Television Festival: “We can make no assumptions about what viewers want or how they want to experience things. We must observe, adapt, and try new things to discover appetites we didn't know were there.”

Kevin Spacey 2013 MacTaggard Lecture at the Edinburgh International Television Festival.

Spacey produced and played the lead in The House of Cards series, which was made according to high film standards. It's so addictive that people often found themselves watching it for weekends on end. The same happened to Breaking Bad and a number of other recent masterfully-crafted series made available online.

The binge viewing phenomenon clearly shows that the audience has no lack of attention span and is willing to watch for hours, provided the films are good.

Experiments with running time

The history of cinema is full of successful examples of filmmakers pushing the boundaries of traditional running time.

In 1983, the radical German filmmaker, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, made a fifteen-hour-plus controversial immersive epic Berlin Alexanderplatz.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Berlin Alexanderplatz (1983) spans over 15 hours.

This powerhouse film garnered a lot of criticism at the time, but to this day it remains a jewel in the renowned Criterion Collection and is a must-see for any aspiring filmmaker.

The 24-hour art installation The Clock (2010) by Christian Marclay explores the flow of time in cinema quite literally. It shows a meditative Ulysses-like montage of thousands of scenes from various films each containing a mention of the specific time that is set to match the real time during the screening. This experimental 24-hour loop itself is a clock bonding real life with the world of fiction.

In today’s competitive environment, films of unconventional length simply get ignored.

The shorter the better

At the other end of the scale, short films by Mélieès, Renoir, Keaton, Chaplin, Buñuel, Truffaut, Marker, Teshigahara, Herzog and Cronenberg have had a massive influence on cinema. Some stories take only a few minutes.

The general rule of editing is to cut out as much as possible without losing the essence. Certain restrictions and time limits often help make content more pure, focused and powerful. What is critical is to make such adjustments with the sole focus on improving the film, not arbitrarily making it shorter or longer.

Festivals and distributors should revisit their policies of acceptable film duration.

Visconti’s The Leopard (1963) was cut by the producers to seven different running times for various markets, from the 205 minute original, down to the 151 minute cut for Spain, essentially destroying a masterpiece.

In today’s competitive environment, films of unconventional length simply get ignored.

The irrelevance of shooting format and running time

Advancements in technology give us a chance to break free from all of the unnecessary bureaucratic limitations. Digital cinema has brought democracy to the industry. We have nearly stopped distinguishing films by whether they are shot on high-end Panavision 35mm film or a cheap prosumer camera.

With internet streaming we are no longer restricted by the length of reels, tapes, DVDs or preset air time. Festivals and distributors should revisit their policies of acceptable film duration. Theater programmers may consider running original sets of selected films of various lengths – a successful practice which existed in the 1930s - 1950s.

Let us set cinema free from marketing limitations and prejudice. The audience does not discriminate based on the film length. It is not the distributor who should dictate the running time, but the very thing cinema is built on – the RHYTHM.

Andrei Severny is a filmmaker and visual artist. Check out his recent article The Theater of the Future Will be in Your Mind.