BY MATT BARONE |

Above the Law: On NEW JERSEY DRIVE's Ahead-of-Its-Time Depictions of Police Brutality

Two decades ago, Spike Lee produced an unflinching look at the one-sided warfare between shady police officers and unarmed black teens. In 2015, it's more relevant than ever.

"It's open season on the black man out here!"

In the 1995 film New Jersey Drive, streetwise teenager Midget (Gabriel Casseus) has every right to say that to his best friend, 17-year-old Jason (Sharron Corley). They live in Newark, New Jersey, which in the '90s was negatively known as "the car theft capital of the world," a reputation Midget and Jason strengthen on a daily basis. High school is a bust, since it takes more than 30 minutes to get through the building's faulty metal detectors, a duration that routinely dissuades Jason from waiting in order to attend classes; instead, he hits the block with his friends, breaks into strangers' automobiles, and goes joyriding. But the car that he and his pal Ronnie (Koran C. Thomas) jack one night belongs to a cop, and the Newark Police Department's Auto Theft division responds aggressively. They fire multiple gunshots into the car, sending Ronnie to the hospital with near-fatal bullet wounds, even though Jason and Ronnie didn't receive any warning or a chance to stop themselves.

Jason flees from the scene unscathed. The next morning, his mother, Rene (Gwen McGee), inquires about Ronnie's hospitalization. Jason replays the events back for her, omitting the part about the stolen car and emphasizing the fact that the cops shot at them despite no justifiable provocation. His mother's reply: "Oh, you need a reason to get shot nowadays?"

Does any of this strike a familiar chord? Of course it does.

Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, writer-director Nick Gomez's New Jersey Drive was ahead of the curve, yet it also wasn't. The disturbing black-teenagers-versus-the-police realities seen in the film, executive-produced by Spike Lee, were prevalent in '95; in today's post-Ferguson society, where Quentin Tarantino's currently being bullied and threatened by police organizations for labeling the deaths of innocent unarmed black men as "murders," those realities are even more in-vogue. Other films have touched on the issue: Do the Right Thing (1989), Boyz n the Hood (1991), Fruitvale Station (2013), this year's Straight Outta Compton, But none have done it as thoroughly head-on as New Jersey Drive.

New Jersey Drive comes from the '90s wave of "hood movies" with killer original hip-hop soundtracks, and much like its peer in that category, Ernest Dickerson's unfairly neglected-by-time film Juice (1992), it's just as worthwhile as Menace II Society (1993) and the aforementioned Boyz n the Hood. New Jersey Drive was Gomez's follow-up to his 1992 indie breakthrough Laws of Gravity, a Brooklyn-set crime drama that earned an Indie Spirit Award nomination for Best Picture; the film's budget was a humble $35,000. Lee, being a fan of Laws of Gravity, recruited Gomez to make a bigger (read: $5 million) picture for Gramercy Pictures, a subsidiary of Universal; for his part, Gomez conceived a rap-centric Mean Streets for the 1990s. Jason and Midget have a dynamic reminiscent of Martin Scorsese's 1973 film's Charlie and Johnny Boy; Corley channels Harvey Keitel's calmer, more level-headed demeanor, and Casseus repurposes Robert De Niro's hot-headed explosiveness.

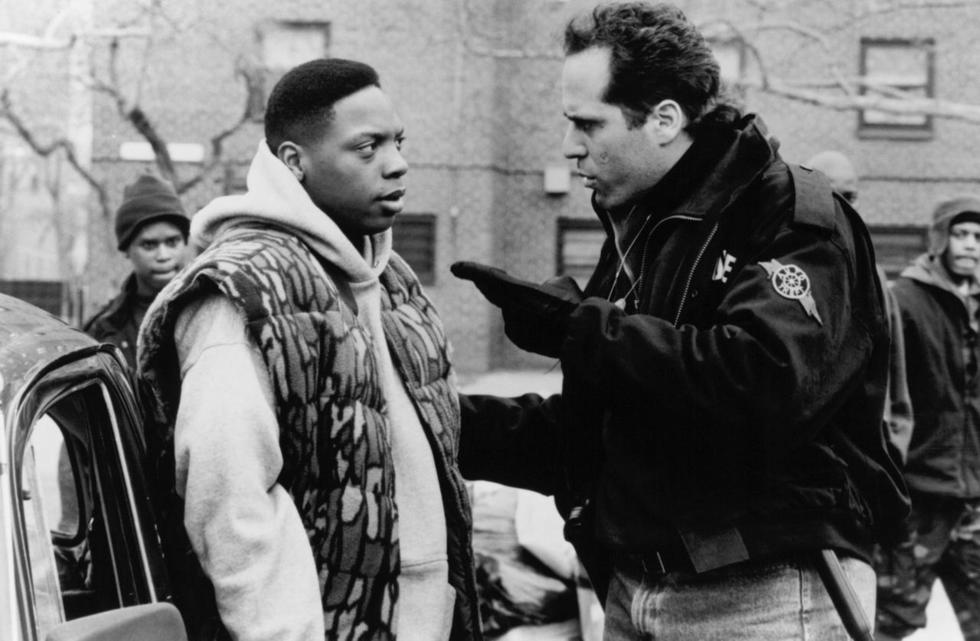

The key narrative difference between Mean Streets and New Jersey Drive is that the latter has a centralized villain: Emile Roscoe (Saul Stein), the hulking, malevolent police officer who's made it his sole mission to terrorize Jason and his friends. Roscoe's evilness isn’t the least bit subtle, due to how Gomez overwrites him into a one-note monster with a badge. In one scene, he brutalizes Jason in a private interrogation room, in an effort to physically dissuade the teenager from snitching on the bigger, more powerful cop—"That's so you stay away from grand juries," he says after landing his final punch.

Revisiting New Jersey Drive today, it's tough to watch Roscoe abuse his power by beating the hell out of Jason and not think about the officers who overpowered Eric Garner as he pleaded with them, repeatedly saying, "I can't breathe." Likewise, it's tough not to visualize Michael Brown's killer, Darren Wilson, when another one of Newark's white cops pushes a weaponless Jason into a cop car, unjustifiably says, "Fuck with me again and I'll blow your fucking head off," and then slugs him with a cheap-shot to the face.

The parallels ring loudest, though, in a pivotal scene involving Jason's rambunctious friend Tiny (played by Clueless-era Donald Faison). The sequence begins like many others in the film: Jason and his crew are standing on a street corner at night, and one of them, Tiny, decides to jack the near whip. Before he's able to drive away, cops swarm them inside their own vehicles with sirens and flashing lights; Tiny, caught off-guard, frantically smashes into the cars parked in front of and in back of his, despite the officers' commands for him to exit the ride. Seconds after Tiny's car breaks free, a cop car bashes into the driver’s side of Tiny's out of nowhere, killing him instantly in front of a stunned Jason and Midget. Just like that, Tiny is dead, never having had a chance to willingly surrender. It's what Quentin Tarantino would rightfully call "murder."

Scenes like that are given maximum impact by how Gomez smartly blurs the lines of guilt. The killing of Tiny isn't figuratively black-and-white. He isn't made out to be a martyr. New Jersey Drive is told largely from Jason's point-of-view, but even he's not thinly defined or caricaturized. The film's cops use excessive force just as irrationally as its teen characters break the law. In Midget's case, there's a sliver of justification. He lifts cars in order to bring them to a chop shop and earn cash—the nicer the car, the bigger the score. To Midget, the fact that he steals the possessions of more financially secure white people is a bonus, because he's the one who's barely old enough to vote yet has to singlehandedly take care of his elderly and sick grandmother, since his parents are no-shows and all of his brothers are in jail. Watching Midget feed his grandma baby carrots, it's easy to sympathize with him.

But Gomez wisely offsets that visual with another that drives home the darkness of Midget's money-acquiring hustle of choice. Slowly driving around a supermarket's parking lot, he spots a white guy dressed in a yuppie's wardrobe and hanging around a posh Lexus; his eyes lit up on the four-wheeled prize, Midget assaults the innocent guy and leaves with his luxury machine. Midget does the right thing at home but knowingly does the opposite in the streets. He's the product of a suffocating and hopeless environment. Earlier in the film, Jason talks to Midget about wanting to get a job. "Who you think you gonna work for, man?" Midget fires back. "Some white motherfucker driving a Lexus while you take a bus?"

Midget's actions leave him seeming tough to forgive, yet it doesn't take long for Gomez to once again distort that perception. New Jersey Drive's climax echoes that of A Bronx Tale, when Calogero indirectly evades death by not getting into his friends' car to join their revenge mission. Jason stays behind as his buddies chase down a group of peers who've stolen his car at gunpoint. Midget, however, leads the charge, and although Gomez doesn't show Midget's final seconds alive, the director's camera slowly revolving around aftermath is emotionally punishing enough. Midget's car has been overturned on a sidewalk, the blood of he and his fellow riders splattered all over the concrete. Jason learns from a TV news report that cops fired 30 rounds into Midget's vehicle, killing him and a pregnant friend of theirs while injuring the other passengers.

The newscaster doesn't need to explain what happened in granular detail; it's obvious. The same white cops who've tormented Jason and Midget all along, most likely led by Roscoe, shot the latter to death without giving him a chance to acquiesce, which Midget probably wouldn't have done anyway, but that's beside the point. A double-digit number of officers shouldn't need to murder three to four unarmed teenagers in New Jersey Drive's fictional 1995, just as those Staten Island cops shouldn't be absolved for ending Eric Garner's life in July 2014. Sitting on his mother's couch and helplessly listening to Midget's death report, Jason represents the millions of people who did the same thing following the news about Garner, or Michael Brown, or Freddie Gray in Baltimore this past April. The list goes on.

Twenty years after New Jersey Drive, it still feels like "open season."

New Jersey Drive is available to buy or rent on iTunes and Amazon.