BY MATT BARONE |

Revisiting Spike Lee’s BAMBOOZLED and Its Endlessly Relevant Themes

Having been regularly slighted by the Academy Awards, Spike Lee will receive a well-deserved honorary statue during tomorrow night's Governor's Awards. In a perfect world, he'd use the platform to promote BAMBOOZLED, his most sadly overlooked film. Here's the case for why it's a timelessly vital piece of filmmaking.

Earlier this week, Spike Lee's 15-year-old film Bamboozled felt uncomfortably relevant. Attribute the feeling to country singer Jason Aldean. Because he either didn't think the situation through or he's just wildly insensitive, Aldean dressed up as Lil Wayne for Halloween and posed for a picture with some friends. His Weezy costume's main ingredient: blackface makeup covered in shades, fake dreadlocks, and with a gold chain dangling underneath.

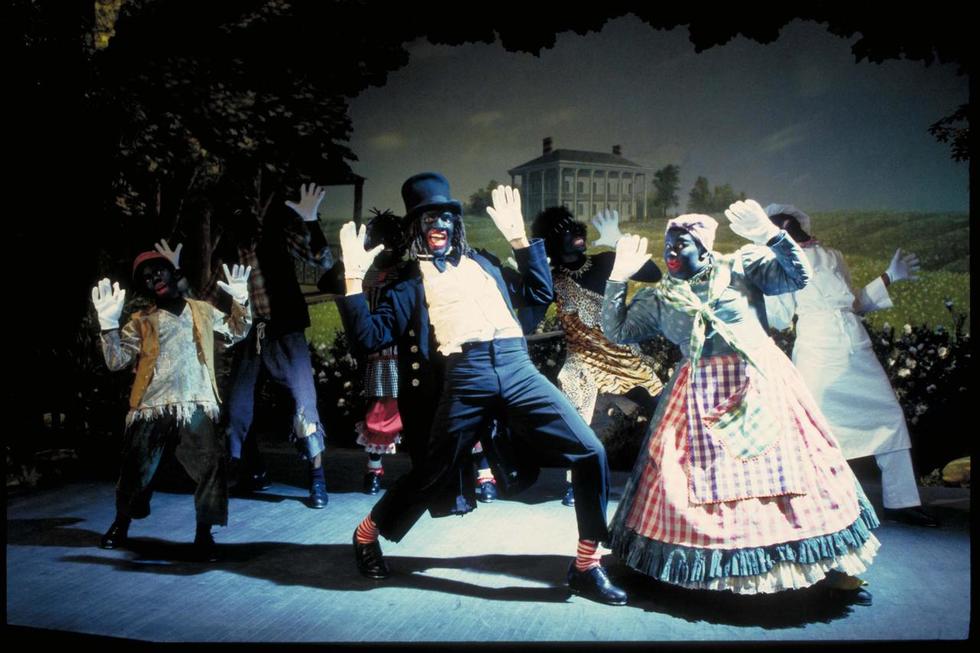

Anyone who's seen Bamboozled can instantly draw the parallels. In that now-infamous Instagram photo, Aldean looks like a fan of Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show, the fictional TV series at the center of Lee's 2000 satire of the media and entertainment industry's handling of race. In Bamboozled, viewers turn Mantan, a variety show in which black actors (played by Savion Glover and Tommy Davidson) wear blackface while shamelessly shucking and jiving and telling pointedly racist jokes, into a ratings smash and start donning blackface the same way fans of The Avengers wear Iron Man tees. Aldean's Lil Wayne costume would be right at home within Mantan's live studio audience.

Unquestionably Lee's angriest work, which says a lot, Bamboozled is a scathing, audacious, flawed, and altogether fascinating lampooning of a problem that's just as prevalent today as it was back in 2000: the misrepresentation of black people on idiot boxes the world over. Damon Wayans stars as Pierre Delacroix, a Harvard-educated producer at the fictional television network CNS; his white boss, played by Michael Rapaport, tells him that his ideas for family-centric programs in the vein of The Cosby Show aren't "black enough." Delacroix, hoping to get himself fired, conceives the most outlandishly racist show possible. When Mantan becomes a mainstream sensation, Delacroix's horror evolves into acceptance, guided by the almighty dollar. But a group of pro-black militants, known as the Mau Maus (played by Mos Def, Charli Baltimore, Gano Grills, and Canibus), including their one white member (MC Serch), aren't happy, and in the film's third act, they get homicidally violent.

According to film curator and critic Ashley Clark, Bamboozled is the quintessential "Spike Lee joint." To celebrate the film's 15th anniversary this year, Clark, 30, has written a short book in which he lays out, in excellently informative and concise detail and skillful prose, exactly why that's the case. Titled Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee's Bamboozled, and released last month by The Critical Press, Clark's monograph resurrects Lee's most underrated effort, firmly placing it back into the film world's consciousness. "I really do think that Bamboozled is Peak Spike," says Clark, who's written for Film Comment, Little White Lies, Vice, and Village Voice. "There are certain things that define Spike Lee as a filmmaker: a lack of subtlety, a fondness for caricatures, an interest in very hot-button social issues, formal and technological experimentation. Those things all crash together in Bamboozled."

The film's cumulative effect is viscerally overwhelming. Lee aggressively crams a multitude of racism-aimed daggers into its robust 135-minute duration. Shot on Mini DV digital video, it's an alien-like curiosity, a major studio release, via New Line Cinema, that resembles an '80s DTV flick aesthetically and reaches levels of thematic rage and darkness that would leave even indie financiers and distributors on edge. Unsurprisingly, Bamboozled tanked at the box office, only grossing $2.5 million on a $10 million budget. There was a basic DVD release in 2001, but ever since then, the film has hardly been a blip on cinephiles' radars. It's never placed alongside Do the Right Thing (1989), Malcolm X (1992), and 25th Hour (2002) on critics' lists of Lee's best or most important films.

Yet its underlying messages remain disturbingly on-point. Back in March, the Writers Guild of America released a report showing that minorities comprise a mere 13.7% of TV staff writer positions, a drop from the 15.6% held in the 2011-2012 season. The study explained that, "Until the recent rise of multicultural dramas like ABC's Grey's Anatomy and Scandal, there had been few successful television dramas that featured a critical mass of minority leading roles or writers… The black-themed sitcoms of the kind that aired on the defunct UPN and WB networks," like Moesha, Everybody Hates Chris, Girlfriends, and The Bernie Mac Show, "accounted for the majority of employed black staff writers."

Lee skewered that troublingly ever-present reality way back in 2000. "Bamboozled has one particularly telling scene," explains Clark, "where Pierre Delacroix comes into the writers' room and it's pretty much 95% white writers, and they hit him with the typical excuses you hear: 'We couldn't find the right people,' and, 'They just didn’t want to do this.' That's certainly still relevant today."

Current television bigwigs would agree. In a recent on-camera roundtable interview for The Hollywood Reporter, six TV showrunners discussed the issue of minimal black writers. Lee Daniels, the muscle behind Fox's predominantly black phenomenon Empire, candidly asked his colleagues at the table if they've hired any writers of color. He learned that Homeland's writing staff, represented by executive producer Alex Gansa, has none, nor does that of Beau Willimon's Netflix series House of Cards. Damon Lindelof, The Leftovers' man-in-charge, kept it all the way real in response to Daniels. "If I'm staffing a show," said Lindelof, "I'm going to get sent 40 scripts for people, and of those 40 scripts, how many of them were written by any people of color? Or women, for that matter? The pool that I'm being told that I should be picking from is a majority white male pool. And if you walk down the corridors of WME, CAA, UTA, you're not going to see a lot of black agents, and they're the ones who [would be] sending me those scripts."

Lindelof's thoughts speak directly to why Bamboozled is finally experiencing a long-awaited and much-deserved reappraisal. "Bamboozled is coming back into people's minds now because they're watching reality television, they're watching Empire, and they're paying attention to what’s going on with Black Lives Matter," says Clark. "I'm not trying to directly parallel Empire with the film's fictional show, Mantan, but Empire strikes me more as a show that Michael Rapaport's Bamboozled character would get really excited about if someone pitched it to him. It seems like his kind of show."

He continues, "The racial climate of the country is profoundly different. Not to say that these things haven't always happened, but the visibility and the awareness of them is at a new high right now, and there are aspects of those things in the film, like the massacre of the Mau Maus at the end of the film by the police, and how the one white guy in the Mau Maus is spared. The time is just right for people to revisit Bamboozled and see how ahead-of-the-curve Lee was."

So why, despite its unwavering relevancy, has Bamboozled been marginalized within its director's filmography for so long? For starters, there's the critical negativity that greeted Bamboozled during its theatrical run. Chicago Reader's Jonathan Rosenbaum called it "sloppy, all-over-the-map filmmaking with few hints of self-criticism"; Roger Ebert attacked Lee's "perplexing" film and predicted that "viewers will leave the theater thinking Lee has misused them." Andrew Sarris of the New York Observer described Lee's attempt to turn blackface into satire as "miscalculated." Armond White, one of film criticism's few prominent black writers, slammed it in the New York Press with, "Bamboozled resembles a padded cell with which Hollywood has provided Lee to bounce off walls." (White's review's headline: "More Trash From Spike Lee.")

The common term used to condemn Bamboozled has been "heavy-handed," a frequently employed barb throughout Lee's 30-year career. But that's unfair. "It's one thing to call a film 'heavy-handed' if it's discussing or putting forth a subject or a point-of-view that we've all seen before," says Clark. "Whenever you watch a Michael Bay film, like one of his Transformers films, you call it 'heavy-handed' because you know what Michael Bay is doing, and you've seen it all before. But I don't think there's ever been another film that so aggressively calls out racism in Hollywood like how Bamboozled does. There are films like Hollywood Shuffle and Tropic Thunder, which are gentle, funny satires of racism and inequality in Hollywood, but I think Bamboozled is frankly out there on its own as a major studio picture. To call it 'heavy-handed,' like so many critics have, is in some ways a get-out clause to not really deal with a lot of the issues it broaches."

Beyond the critics, though, everyday movie lovers haven't quite waved the Bamboozled flag for Lee either. But in their case, it's easy to see why. "It's a film that holds Hollywood and the establishment accountable in the present and in the past," says Clark. "It aims to call out racism, which happened 100 years ago and is still happening today. It used satirical methods to do that, but it definitely leaves people feeling uncomfortable. Because it's so full-on and so excessive, in a way it becomes an easy film to dismiss. It's such a feel-bad movie—it has no intentions of leaving you feeling uplifted."

Like all of his films, Bamboozled is pure Spike Lee, all the way through. The Brooklyn-bred filmmaker's opinions, however polarizing and heated, course through its filmic veins. "Spike Lee has been the lone guardian of black cinema for three decades now," says Clark. "I'd love to just call him a 'filmmaker,' right, minus the 'black' identifier, because that's what he is, but there's no other black filmmaker who's had the prolific career that Spike Lee has had. He has courted controversy at times, no doubt, but he's also been hit from all sides. Bamboozled was an outpouring of that; it was his two-middle-fingers-in-the-air gesture to the world. It's kind of a 'fuck you' to everybody. He was being tagged in the press as an 'angry black man,' as well as a 'racist' by idiots, both of which still happen today. I'd imagine it's really difficult to be Spike Lee—all you have to do is look at the Chi-Raq controversy."

Chi-Raq, of course, is Lee's next film, scheduled for a theatrical release on December 4. It's the first original release from Amazon Studios, which makes it a front-page talking point for film journalists, but that's not the biggest figurative target on Chi-Raq's back. A modernization of the Greek play "Lysistrata," the film imagines what would happen if all of the women in the notoriously gun-ridden Chicago refused to have sex with the Windy City’s men until they put down their weapons and get along. In other words, as the film's tagline states, "No peace, no piece."

From the second it was first announced back in the spring, Chi-Raq has been chastised by many Chicago residents for, in their eyes, mining laughs out of their home's deathly serious problems. The debut of the its first trailer last week amplified the outrage, presenting a raucous film in which Samuel L. Jackson flamboyantly narrates, Dave Chappelle cracks jokes about stripper poles, the usually squeaky-clean Nick Cannon plays against type as a hardened thug, and themes are hammered in with sing-songy dialogue and defiant choruses.

Less than a week after Chi-Raq's trailer's launch, Lee indirectly channeled Pierre Delacroix. He released a clip from the film along with an introduction, in which Lee fully, albeit defensively, explains the film's intent. "There's this absolutely extraordinary parallel between Bamboozled and what's going on with Chi-Raq," says Clark. "Damon Wayans' character literally opens Bamboozled by defining the word 'satire.' The reason Spike gave for that was so that nobody would mistake Bamboozled for an attempt at realism. But now, by coming out with that second Chi-Raq trailer, Spike Lee has done exactly the same thing that Damon Wayans' character does. He had to tell people, 'Look, Chi-Raq is a satire.' It's amazing that media literacy levels aren't high enough for people to know whether something's satirical or not. Spike has always been aware of that."

Which begs the question, how would the world react to Bamboozled today, if Lee had waited 15 years to unleash the fury? It'd probably make the Chi-Raq uproar seem tame. "I dread to imagine what would happen if a film like Bamboozled were released in today's climate of think-pieces, counter-think-pieces, and Twitter storms," says Clark. "A few months ago, I tweeted something where I asked, 'What's the one movie that you're glad came out before today's think-piece climate?' Somebody mentioned Pulp Fiction because of its controversial content, but then someone else tweeted, 'All of them,' and that pretty much ended the discussion."

He adds, "My own personal answer to that would be Bamboozled."

The Internet would probably collapse at the weight of the endless think-pieces it'd inspire.

Ashley Clark's Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee's Bamboozled is available now, via The Critical Press.

BONUS: The video for the Mau Maus' "Blak is Blak," from Bamboozled's soundtrack: