BY MATTHEW ENG |

Travis Bickle’s City of Strangers: Looking Back at TAXI DRIVER, 40 Years Later

A deep-dive into Martin Scorsese’s urban inferno on its 40th anniversary.

Warning: spoilers to follow.

Some films capture you almost instantly.

There's a sudden shiver of dread but also enticement that rushes up my spine every time Taxi Driver’s title sequence seeps onto the screen. The crown jewel of Martin Scorsese’s career begins with a cloud of steam, rising as though from subterranean levels and enveloping a night sky dotted with endless street lights. A generic yellow cab sails through the smog, bathing in it and carrying in the luridly red neon-lettering of the title, while Bernard Herrmann’s somber, sax-kissed score lulls us into this battered cityscape.

The New York City of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver is a declining metropolis in the midst of self-corrosion, a big city whose bright lights shine on much seamier subjects than multi-tiered retailers and GoPro’d tourists. The lights radiate from the glowing marquees of the 24-hour porno palaces that fill Times Square and the penetrating headlights of taxis that wander the city’s forbidding streets. They signal a different kind of New York City, one that has transformed into a menacing lair of grit and grime, its litter-strewn sidewalks populated with slum queens and young guns, druggies and dealers, hustlers and hookers. Scorsese all but begs us to ask ourselves, Is this a city in dissolution or is this the underworld itself?

Taxi Driver is first and foremost a nervy and nuanced character study, but it's furthermore the study of a city, one that remains just as riveting and dynamic a force as the film’s eponymous protagonist. Travis Bickle (indelibly inhabited by Robert De Niro in the greatest male performance of the 1970s) may be the tender, tormented antihero of the film, but even he would remain an inaccessible and insignificant creation without the bruised, burnt-out New York City, a subject that's just as centralized in the film's immediate focus as Travis. From performance and production design to script and score, Taxi Driver is a galvanizing dual portrait of a crumbling city and the lost soul who is desperately bent on clawing his way out from the deepest depths of this urban inferno.

It’s difficult to grasp nowadays just how revolutionary a cinematic creation Travis Bickle was when Taxi Driver first premiered, what with all the lame, derivative avatars the character has spawned throughout the years, to say nothing of all the clones the film itself has given rise to. The first image of Travis comes during the film’s opening sequence as a pair of roaming eyes stare out at the rain-slicked streets of the city, so vivid as if rendered from gaudy watercolor. But these are not the eyes of some floridly mad-eyed menace, in the vein of, say, Falling Down's Michael Douglas or Nightcrawler’s Jake Gyllenhaal.

Instead, when we first really meet Travis, he is a gangly, smirking Vietnam veteran in a rumpled military jacket, looking for a job driving cabs to cure his sleepless nights, a man who is too shifty to trust but just casually charismatic enough to crack wise with an unappreciative personnel officer. One look at this lanky, simpering boy and it’s impossible to imagine him lasting more than a week in combat. As scripted by Paul Schrader, Travis is a character who constantly defies our expectations about what a film’s protagonist can do and can be, a character who is many, wildly antithetical things, often all at the same time, "a walking contradiction," as one character will later label him. Further deepening the persona is De Niro’s masterstroke of a performance, indicating what is undeniably poignant and yet potentially dangerous about a man like Travis Bickle.

Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman waste no time in similarly fleshing out the city that Travis part and parcel of, yet so thoroughly detests. However, rather than taking the expected, well-worn route of setting their film in some broad, perpetual darkness (a choice that Travis’ night owl nature would have at least permitted), both artists instead strike a delicate balance between night and day in this entropic city. They allow for the deep, dark shadows that a film like this requires, but also prove more than willing to keep the lights on. Chapman utilizes consistently utilizes natural light so as to suggest what might be alarming about a pimp who conducts his business from in broad daylight, or conversely, what might be inviting and even hopeful in this disintegrating city about the sunny offices of a presidential campaign’s headquarters and the object of Travis’ affection who sits inside.

Aided by Marcia Lucas, Tom Rolf, and Melvin Shapiro’s mesmerizingly fluid edits, the film simultaneously constructs Travis and New York’s characters by interweaving the two, allowing one element to inform the other in ways that are scripted and stylized. Character is found in all directions and areas of this vast urban landscape and further accentuated by key stylizations. These choices can be heavily pronounced, like the hell-red filter that suffuses many shots of the city’s grotty nighttime streets. But they can also be subtle, even invisible, like the way the coffee shop where Travis holds his first successful date with Cybill Shepherd’s wholesomely glossy campaign worker Betsy is enhanced by warm, fuzzy sunlight and the din of urban hubbub that weaves in and out of their intimate interaction.

It's this sort of intimate yet abbreviated interaction between two individuals attempting, but ultimately failing to, find some kind of deeper connection that reveals something gentler, but no less troubled, about Taxi Driver. It's remembered today as a searing document of the treacheries of '70s-era urbanity, which, to an extent, it is, but Taxi Driver is also the story of a man seeking some form of salvation from a city that has expended all his faith. Travis is left to interact with this city, engaging with its seamiest pastimes, less for gratification than to understand their appeal. Travis’ frequent, stoic trips to porn theaters are marked by a sense of restless, innocent curiosity that ultimately backfires when he drags doe-eyed Betsy to a dirty movie on a terribly misconceived second date, unintentionally humiliating her in the process and botching any future chances with her. Travis is always something much deeper than a one-note lunatic who’s missing more than a few pieces: He’s a man trying to forge a bond with New York City, often through attempts than are exceedingly misguided and wrongheaded.

Taxi Driver suggests that these types of connections are ultimately impossible within such a fractured urban arena and especially for someone as equally fractured as Travis. He doesn’t so much desire pretty, put-together Betsy in any overtly sexual manner as much as he worships her purity and thus clings to her like some golden-haired manna in his run-down wilderness. This idolization overpowers the import of any actual, physical attraction to her, ultimately setting the stage for this infatuation to quickly escalate into a vicious obsession with an entirely different object.

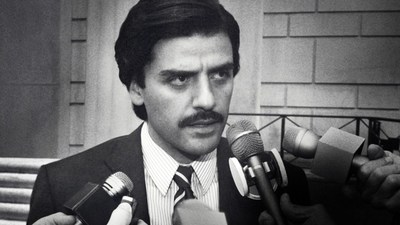

Senator Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris), the presidential candidate whom Betsy works for, becomes the centralized point of Travis’ righteous anger after losing Betsy, but he also remains a purposely ambiguous figure throughout the film. In a scene before the disastrous second date with Betsy, Travis finds himself driving the senator to a campaign event, a coincidence that Travis takes quick advantage of when the ever-campaigning senator asks, "What is the one thing about this country that bugs you the most?" The question incites something deeply resentful within Travis, who proceeds to ramble with blazing embitterment about the current state of this city as the senator looks on, obscured in shadow: "This city is like an open sewer. It’s full of filth and scum. Sometimes I can hardly take it." Scorsese, ever the conflicted Catholic filmmaker, films the encounter with the same agitated tension of a church confessional, as Travis reveals the sins of the city and the barely concealed rage they cause him to a stranger on the other side of a safety screen, a powerful man who offers assurance but no real solutions.

It's only after being spurned by Betsy that Travis finally allows himself to slowly succumb to the “filth and scum” of the city by buying an arsenal’s worth of firearms and devising a delusional plot to assassinate the senator. We watch as Travis trains in his grimy apartment, sculpting his body into an impenetrable block of steel and adopting the same violent behavior that he has observed from behind his windshield. He becomes the nastier, more homicidal creature that Scorsese has signaled from the outset. When a fellow cabbie tags the nickname "killer" to Travis early on, we know it can’t only be for irony’s sake.

Scorsese and company depict a convincingly horrific city that is itself the seedy source from which Travis’ escalating hatred emanates. As Scorsese himself wrote in an essay on the film in his book Scorsese on Scorsese, “[Travis] chooses to drive his taxi anywhere in the city, even the worst places, because he feeds his hate,” a hate that resonates in myriad ways throughout the film. It's a sexualized hate, as Travis' clean cab is constantly soiled, both literally and figuratively, by a middle-aged man (played by Scorsese himself) describing in detail exactly how and where he plans to shoot his unfaithful wife, or a hooker and her client engaging in a quickie in the backseat, which is immediately followed by a shot of Travis diligently wiping the fluids away. It's also unsettlingly racialized, as in a slow-motion shot where Travis scowls with suspicion at a passing group of black men, or in a pivotal scene where Travis wastes no time in offing a black armed robber underneath the glaring lights of a neighborhood bodega, his half-cloaked racism being probed even deeper.

And, still, it’s the unconquerable loneliness of Travis that comes to define his descent into madness, at one point even alluding to Thomas Wolfe by describing himself “God’s lonely man.” Travis is a loner in a city of millions, a nobody with big, impossible dreams of attaining something close to actual personhood. It is this loneliness that compels him to latch onto women whom he would remain invisible to were it not for his own obsessive impulses, first with Betsy and then later with Jodie Foster’s notorious Iris, a 12-year-old child prostitute. Travis first spots Iris in his rearview mirror, a nameless and nearly faceless young girl cowering within the shadows of his backseat, begging him to drive before she is dragged away by her pimp. In one of the film’s most haunting shots, Iris stands frozen and fearful in the glare of Travis’ headlights after he nearly runs her over, a child in halter top and hot pants. It’s an image that sears itself into Travis' memory, compelling him to find her and setting him on a path to become the manic and mohawked avenging angel that remains the character’s most recognized incarnation.

Both Betsy and Iris follow similar dramatic trajectories in their relationships with Travis: They are initially bewildered by the overtures of a man who disconcerts but also intrigues them and who persuades them to go on similar daytime "dates" in coffee shops. However, both women have been placed on totally opposite ends of Travis’ warped Madonna-Whore spectrum. In Travis’ eyes, Betsy and Iris are not fully functioning human beings so much as occupants of very specific roles that Travis has carved out for them, i.e. a deified lifeline and a scandalized damsel in distress. It becomes clear in his meetings with Iris, during which Travis directly and incessantly implores her to stop prostituting, that Iris has not merely caught his attention but also sealed his fate.

After failing to assassinate Palantine during a public rally, a mohawked Travis makes his way to the squalid tenement-cum-bordello in which Iris lives and works and the film culminates in a relentless, protracted bloodbath that, as scripted by Schrader and staged by Scorsese, reaches near-operatic levels of carnage. Only Travis and a petrified Iris are left standing by massacre’s end, whereupon, having "rescued" Iris, Travis attempts to commit a Samurai's death by shooting himself in the head, only to find that he is out of ammo. Bernard Herrmann’s sonorously mournful score accompanies the scene like a processional as a cop enters the room and aims his gun at Travis, who cocks his bloody index finger against his temple and fires away with an iconically insolent smirk. He throws his head back with a look that lives somewhere between triumph and resignation as an overhead tracking shot transports us beyond the blood-stained walls of the building and into the streets. We see a mob of gathering bystanders crowding the scene as police cars bathe them in flashing red lights, an eager audience for the squalid spectacle that has occurred inside.

What follows is an ending whose meaning has always been elusive in its deliberate blurring of reality and fantasy and yet is all the more fascinating precisely because of this legendary ambiguity. As Travis drops off an admiring Betsy on the curb in front of her home and drives away in his taxi, it is clear, no matter the hazy, illusory quality with which the scene unfolds, that Travis has at last achieved not just a higher form of recognition, but actual personhood. The retributive and ultimately cathartic bloodshed of the climax has spawned a real human being, if only within the imaginary landscape of a deteriorating mind.

This is the closest thing to paradise that a misfit like Travis Bickle could ever hope to reach. And the ultimate, unforgettable tragedy of Travis, as well as Taxi Driver, is that it all may be a dream.