BY MATT BARONE |

Justice For Some, Not All: The Powerful Story Behind the Can't-Miss Documentary SOUTHWEST OF SALEM

If you thought MAKING A MURDERER was infuriating, wait until you watch this remarkable true crime documentary, premiering in Tribeca 2016's Viewpoints program.

Accusations of witch covens, human sacrifices, and cult-like mania—you'd think those were elements in a 17th-century-set story like The Witch, not a documentary covering something that happened as recently as 1994. Yet those all at the center of Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four, the provocative new documentary from Austin-based director Deborah S. Esquenazi.

Part of Tribeca 2016's Viewpoints program, Southwest of Salem details the trial and long-term imprisonment of four Texas women—Anna Vasquez, Liz Ramirez, Cassandra Rivera, and Kristie Mayhugh—who, in 1994, were accused of sexually abusing two pre-teen sisters, Stephanie and Vanessa Limon, and subsequently locked up behind bars. Although the women maintained their innocence, they were ultimately powerless against a multitude of forces and factors, all of which revolved around the fact that they're lesbians and had the misfortune of getting swallowed up by the court system at the height of the "Satanic Panic" hysteria that swept America in the early 1990s; people who drank the figurative Satanic Panic Kool-Aid believed that ritualistic abuse was infecting their neighborhoods, and that gay men and women under Lucifer's control were the most likely culprits.

In Southwest of Salem, Esquenazi, a rookie filmmaker with past experience as a journalist and radio producer, gives the "San Antonio Four" the chance to proclaim their innocence while painting a disturbing and maddening picture of seemingly non-guilty victims being dominated by police and courtroom biases. Not unlike Netflix's recent true crime phenomenon Making a Murderer, Southwest of Salem leaves its viewers furious about the criminal justice system's ability to manipulate the truth to its own liking.

To further tell their own stories, all four women, if all goes as planned, will be at the film's Tribeca dates for post-screening Q&As. For now, though, Esquenazi remains their loudest supporter. Here, she recounts the fascinating story behind how she became an advocate for the "San Antonio Four," how Southwest of Salem shines a light on injustices suffered by the LGBT community, and why mass hysteria can be scarier than Beelzebub himself.

How did you first come across the story of the "San Antonio Four"?

It all started with my colleague Debbie Nathan, who's an investigative reporter and writes a lot for The Nation. When I first started as a journalist, I was as an intern at the Village Voice, and she sort of became my mentor there. Shortly after I left New York in 2010 and moved back to Texas, she called me and said, "You have to take a look at this insane case that's coming out of San Antonio," which isn't far from where I live in Austin.

My first reaction was, as you can imagine, "I don't want to touch that." The only coverage available was this incredible article in the San Antonio Express News, by a reporter named Michelle Mondo; she laid out this incredibly complicated saga. But Debbie Nathan kept circling back with me. She wrote the book on the Satanic Panic era, titled Satan's Silence, and also famously helped investigate the case that became the film Capturing the Friedmans, so she absolutely knows a great story, and she also has a passion for social justice.

At the time that I was rejecting telling this story, I was in the process of coming out as a lesbian. I was having a really tough time. Debbie was smart to frame it as, "This could be you now." Because of Debbie, I studied the case and read all of the transcripts, which were remarkable and chilling reads; they're upsetting and incredibly homophobic. Then I went and met the women, and that took several months. My first interview with Anna really started things for me and this project; as you can see in the film, she's so powerful and earnest. That combination of meeting the women in person and reading the transcripts really got me—at that point, I was committed.

Were there any moments or revelations early into the filmmaking process that surprised you, and/or changed the game for the story you wanted to tell?

What’s really crazy is that, as I started studying the case, there were no mentions from the media perspective about Anna and Cassie's relationship. Although I don't know exactly why, my hunch is that it was easier to demonize them. They were painted as these single and predatory monsters, as opposed to what they really were, which was a committed, loving family.

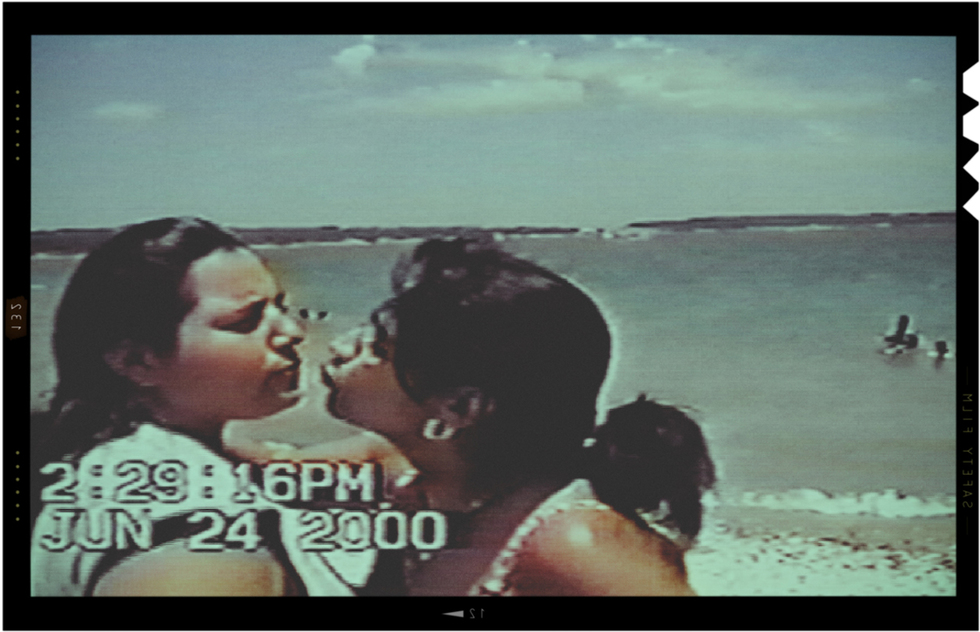

At the time, I was teaching radio documentary to teens in Austin; we'd work with high-risk teens and help them produce radio stories about their lives, which I loved doing. Because of that, I was really interested in doing the "San Antonio Four" as a radio piece, but I wasn't able to get people to believe there was a story there. It was rejected everywhere. But in January 2011, when I first saw the VHS tape of Anna and Cassie together in love, I thought, "Wait, we have a film here." I was actually going to do it as a short film, but then I recorded Stephanie Limon's recantation on tape—that was the most chilling experience of my life. I'd already been in the prisons and gotten to know the women and heard their stories, but it didn't feel like, "Holy shit, we have a massive break in this story," until Stephanie recanted on camera.

Once that happened, a buzz about it started in San Antonio and Austin. Local networks started asking our documentary team, "Are you willing to share any of that footage?" We said, "Yes! We'd be more than happy to!" Maybe sharing your documentary footage upfront isn't necessarily common, but my goal was to get these women out of prison. In fact, that was sort of when the film became a part of the process of getting these women out of prison. And suddenly we had this piece of precious recantation. That was when our film became more than just a background story—now we have this massive new conflict and a plot twist.

That moment reminded me of Errol Morris' The Thin Blue Line. It gave me that same chilling feeling. That's when I thought, "Oh my god, we've got something really big here."

Did that change your overall approach to the story, then?

We decided to take a participatory approach to documentary filmmaking. I started to create allies within the queer communities in Austin and San Antonio, and we started to showing them some raw footage from the prisons and of the recantation and interviews; we'd show that footage to a bunch of people in warehouses with shitty screening rooms, and that suddenly created this activism of, "We have to get these women out of prison." It started off with about 30 people, and then our biggest screening had 250 people, with standing room only and a line out the door in San Antonio.

Part of why I did that was because I have some discomfort with the issue of agency when it comes to film. This is not my story to tell, so by showing footage of the women in prison talking about their case, I could kind of remove myself. That became a way in which people started reporting about the case; they'd all go to those screenings, watch the raw footage, and learn about the case. You could feel the buzz in the air.

Our hope now is to exonerate the women, but back then, when we held those screenings, we just wanted to release them from prison.

As the momentum kept building, and the local queer communities joined your cause, I'd imagine that your dedication to the story only increased, since you're also a part of that community.

Absolutely. This case really is about homophobia. I don't want to speak for all gay-identifying people, but there is this sort of underlying fear that we have and share, as gay men and women, that people think we are predatory child abusers. A lot of people have stood up and said that to me. By seeing how I deal with that [fear] myself, these four women were able to trust that I'd have a sense of care about their story, and I really do. That kind of pernicious feeling of, "Gay people are more predisposed to harming children," is such a falsity, and it still exists. Right after DOMA (the Defense of Marriage Act] was struck down, I heard Texas council members say, "Congratulations, we're now allowing child abusers and child rapists to marry each other." I can't believe that's still something people say.

It's scary when you realize that the ways in which people condemned gay men and women during the Satanic Panic craze during the '90s isn't that much different than how the LGBT community gets demonized still today. Satan's no longer the universal cause, but the underlying sentiment remains the same.

Hysterias still exist well beyond the Satanic Panic era—we can talk about them in regards to anti-Muslim sentiments, or in regards to police brutality. When you're in a hysteria, it's hard as a culture to see that you're in one. So of course we look back 22 years later and say, "I can't believe we indicted so many innocent people." The McMartin case, which there's footage of in Southwest of Salem and dealt with preschool kids, was, at least at the time I was researching it a few years back, the most expensive criminal trial in the history of the United States. Those women were in their 60s and 70s, and the allegations against them said that they'd sexually harmed children—while in their 60s and 70s! They were grandmothers!

We look at cases like that now and say, "Oh my god, I can't believe we did that." But when a culture is in the midst of a hysteria, it's hard to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

The recent horror movie The Witch, which is set 400 years in the past, is all about how religious beliefs and fears can lead to a similar kind of demonization; the issue remains, whether it's the young women burned at stakes in olden times or the gay people who are attacked today. Some things never seem to change.

The cycle continues, and it's troubling. Before I started researching this case, I'd known about the Satanic Panic era because of the Paradise Lost films and Debbie Nathan's book, Satan's Silence. But through my research, I realized that there's an under-discussed side to that era, and it’s the underlying homophobia. The Bernie Baran case is a great example; he was 18 years old and had just come out as gay, and he was indicted and sent to prison.

I also lived it. I grew up in Texas during that era; I remember hearing the discussions and receiving these flyers that warned people to stay away from "these Goth teens" and "devil worshippers." It was part of my culture growing up. But looking at it now from a critical perspective, I can step back and see all the little pieces as they come together into this massive puzzle.

In the film, Debbie Nathan says the San Antonio Four's case was the Satanic Panic era's "last gasp." Do you think there's any specific reason why this case helped to signal the end of that hysteria?

From the research, and from what I do remember, several of those cases did result in indictments, but then some of them were later overturned on appeal. So there was a kind of reversal of thought, where people started becoming more critical of how the police and district attorneys were using Satanic Panic as a way to indict people. But these four women just fell through the cracks. It's interesting to ask the question, "So why did these four women fall through the cracks?" And that's what Southwest of Salem does. We have our theories, and we present them in the film.

What's interesting about this case, and it isn't something we talk about in the film, but it's something to think about, is that, when these women were first investigated under the allegations, a homicide detective investigated it. Homicide detectives always go into a crime scene knowing that a crime has been committed. It's not a question of if a crime has been committed—a crime has been committed; there's a dead body. When you have a homicide detective starting to investigate a case like this one, the question of "If?" and the faculty you use to ask the question, "Does this make sense?" aren't really applied. That's another twist to this case, but it just wasn't clicking in the editing room for us. But it's something I plan on talking about more as the film gets out.

Southwest of Salem is coming on the heels of Serial and Neflix's Making a Murderer, both of which tapped into the current zeitgeist in really big and profound ways. Your film and Making a Murderer, in particular, both cover cases of wrongful imprisonment and how the system can crush people who are helpless against it. In your opinion, why are these kinds of true crime documentary stories so popular right now?

Right now in our culture, we're having this healthy suspicion and questioning of our justice system. I think we have to go back not only to the roots of policing but also how prosecutors are actually presenting these cases to jurors. What we really wanted to do with this film was explore the mythology of how the jury was played. Part of it was exploiting the fears that, "See, these are four gay women, and this is a highly sexualized thing." When you go really deep into the transcripts, they're so bizarre, and they're highly sexualized.

There's a question of, "Did the prosecution over-sexualize this case?" Specifically in Liz Ramirez's case, because she was tried first, they enhanced the sexual parts to make the jury really uncomfortable; it's easier to indict someone if their case is pinging the most uncomfortable parts of your own sexuality. If we did a series like Making a Murderer, I would've done a whole episode on Liz Ramirez's trial alone, which, by the way, I still might do as a short film. Liz's case is an endlessly fascinating exploitation of mythology, in the way that they argued it. And she got 37.5 years—that's crazy!

There's a quote in Southwest of Salem that perfectly sums things up; it's from Jeff Blackburn, an attorney for the Innocence Project of Texas: "If people only knew how little truth and justice have to do with how the legal system works, they'd probably amass in front of courthouses with lighted torches."

That quote is actually prophetic, too. Barely two years after he said that, Ferguson happened. I can appreciate that Jeff really understood how fucked-up the system is. In his effort to be political, he really pinpointed all of the nuances that have been working against the tide of justice in our country.

Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four will have its world premiere on Friday, April 15, at 5:30 p.m. Additional screenings will take place on Sunday, April 17, at 7:30 p.m.; Monday, April 18, at 3:30 p.m.; and Wednesday, April 20, at 8:30 p.m. Buy tickets here.