BY MATTHEW ENG |

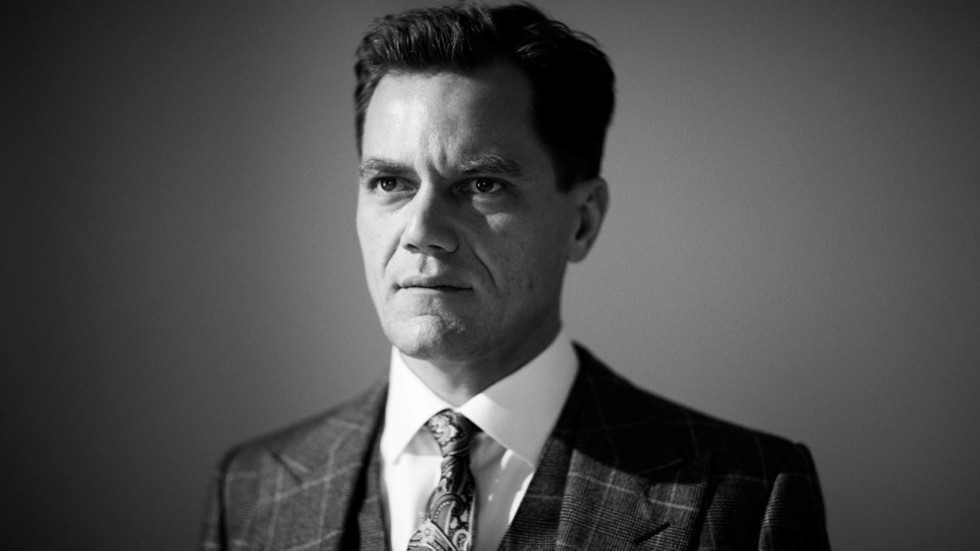

Becoming the Actor's Actor: Why Michael Shannon is a Tribeca 2016 MVP

One of the industry's most admired actors talks to Tribeca on the eve of the Festival, where he headlines three world premiere titles.

There's a searing, protruding look in Michael Shannon's eyes that charges even his less intimidating characters with an instantly potent authority. You know the look. You've seen it countless times, in various formations, within the past decade: in 99 Homes' housing mortgage mercenary, Boardwalk Empire's renegade Prohibition agent, Man of Steel's flamboyantly zealous General Zod, Take Shelter's suburban clairvoyant, or Revolutionary Road's asylum-bound provocateur, the role that earned him a surprise Oscar nomination in 2009 and spurred a career boost that has since lifted him to the upper ranks of the American acting elite. When Michael Shannon appears on a screen, you straighten up and pay attention.

Shannon, who's currently starring in frequent collaborator Jeff Nichols' intriguing, ground-level sci-fi drama Midnight Special and in an all-star Roundabout Theatre Company's revival of Long Day's Journey Into Night, has fostered a unique actorly identity. He feels strikingly reminiscent of performers like Peter Falk, Al Pacino, Geraldine Page, George C. Scott, and Cicely Tyson, '70s-era thespians who continued to zigzag across film, theater, and TV even at the heights of their film stardom. And Shannon's film career, which has come to encompass indies, prestige pictures, and big-studio tentpoles, shows no signs of slowing down.

At Tribeca 2016, Shannon appears in three films that draw upon his magnetic intensity in new and exciting ways. In Bart Freundlich's coming-of-age sports drama Wolves, he's a good-time dad with a crippling gambling addiction; in Robert Scott Wilde's surrealist caper Poor Boy, he's a burnt-out rodeo clown dueling with his deadbeat grifter son; and in Liza Johnson's rollicking Gala selection Elvis & Nixon, Shannon takes a veritable, vivid acting cliff-dive as a late-age, hard-partying Elvis Presley during his weird, real-life meeting with Richard Nixon.

Shannon sat down with Tribeca to talk his three Tribeca selections, the indie industry's not-so-promising transformation, and what stokes his creative energies most these days.

You have three films premiering at Tribeca this year. You're still doing publicity for Midnight Special and in previews for Long Day's Journey. And that's not even taking into account your very busy 2015, or the ten or so films that you have coming down the pipeline. Do you get enough sleep?

I get as much sleep as I need. I haven't collapsed yet. I mean, even if I wasn't working, I probably wouldn't get much sleep because I have two young children, so they have a tendency to wake you up in the morning.

Are you directly seeking these projects out or are the offers finding you nowadays?

People are tracking me down and asking me if I would consider this, that, or the other thing. The films I have in the Festival are the results of people adamantly saying it would be nice if I was involved. But I had trepidations about [Elvis & Nixon], because I wasn't entirely convinced that me playing Elvis was a pretty good idea. And I was intimidated by Wolves just because the character was so dark and it didn't seem like it would be a lot of fun. But the directors and producers were very persuasive. Ultimately, I wound up being glad that I did both of them.

How you did you initially become involved in Wolves?

I did a movie called Freeheld with Julianne Moore. We were buddies and we text each other every once in a while. One day, I got this text saying, "Hey, would you consider looking at my husband's screenplay?" So it started there. A lot of the script—this part—really seemed like a drag. I was just gonna leave it because I had been doing a lot of pictures. But then Bart said, "Well, let's just have lunch and talk." I had lunch with Bart and I was very moved by how much the project seemed to mean to him. It seemed to be a very personal movie for him, a labor of love. Bart's just a really charming guy. A good person. I'm very easily persuaded when the person I'm going to be working with is just a decent human being.

Since Take Shelter, you've been a part of a number of credible and lived-in familial ensembles, a tradition that continues into Wolves, Midnight Special, and even Long Day's Journey. What goes into building a compelling onscreen family and making such a unit and its numerous dynamics believable?

It has to happen very quickly. It's not as if you get a bunch of time to go and hang out before you start working. I think it's about being open and aware to other people. Being less concerned about yourself and more concerned about making those connections. A lot of times, acting can tend to make people very focused on themselves. I try to not worry about, Oh, am I doing a good job? Do people like me? It's about what can I do to help these other people do their jobs. It’s kind of a mysterious thing because it can go sour. I feel like I've been a little bit lucky to work with kids like Jaeden [Lieberher] in Midnight Special and Taylor [John Smith] in Wolves. I liked both of them right away. Their heart was in the right place; they were really devoted to the movies and their parts. So a lot of it is very instinctual. There's not a construction manual for it.

When you're playing a character as dark and potentially unsympathetic as the one in Wolves, are you ever concerned about making sure your character’s actions and intentions are readable to an audience?

I leave that up to the directors. They're the ones who have decided what the story is. I just try to get into [the characters'] circumstances and live in it. I never try to walk away with the picture. I just try to be whatever that person is, as much as I can. And I feel like everybody has their good points and their bad points. Even the dad in Wolves, he's not totally reprehensible. He's just made decisions that have made it hard for him to be a good person anymore.

In Elvis & Nixon, you're playing one of the most inarguably iconic American figures who ever lived. How important was it, for you and director Liza Johnson, that your Elvis be distinctive to audiences?

The person I really give the most credit to is Jerry Schilling, the actual Jerry Schilling. [Editor's note: Schilling is a famed member of Elvis' entourage, the "Memphis Mafia," and is portrayed in the film by Alex Pettyfer.] Jerry was very involved with the picture. I spent a lot of time with him, and so did Liza. During my talks with Jerry, he would just keep reiterating how important it was to him that we give his friend some serious consideration and not just do an impersonation.

Elvis did a lot of mysterious things. This meeting [with Nixon] was a very mysterious thing. Jerry knew Elvis as well as probably anybody and he's still not entirely sure why he did it. He can only kind of speculate. So it was one of our main concerns to unravel those mysteries and take Elvis seriously.

Does your approach to a character change in any significant way when you're tackling a role as larger-than-life as Elvis Presley, as opposed to one rooted very distinctly in a recognizable reality, like your parts in Wolves and Poor Boy?

Elvis was definitely real. I don't think he was a fantastical, phantasmagorical thing. He was a real guy doing something real. That's what I was trying to do. I spent all day, when I was at work, watching the interview that Elvis did for [the 1972 documentary] Elvis on Tour and used it in the movie. Jerry had the interview and he let me listen to it. I would listen to it all the time. It was great, for a number of reasons, because I could hear his voice all the time. But it was also a pretty revealing interview. It was good because it was Elvis behind-the-scenes, not in front of people, not his public persona, but very conversational. He wasn't trying to impress anybody.

You're one of the exceedingly rare actors who has managed to maintain his personal privacy in a highly public business. Is such anonymity integral to your being able to disappear into roles?

Obviously, I look, like, a very certain way… You know, I'm not gonna blend into a crowd. I believe in approaching everything with as much humility as possible. I started out in this business 25 years ago, doing plays and not making a dime. I never really learned how to do this stuff. So, I figure as long as I never lose sight of that…

Do you still feel most comfortable working in the indie world?

I really like the big movies. I had a blast on Man of Steel. I don't necessarily mind doing big movies. But, honestly, a lot those scripts aren't any good. It's pretty fascinating how much money people will spend to make really crappy films—that's really what it boils down to. In terms of the experience of being on set, I'm not really looking at it like "indie this" or "studio that." I just want the good writing. And for whatever reason, a lot of the really fantastic scripts don't have big studios behind them.

I feel like I got really lucky with Man of Steel because, you know, that's authentically a comic book movie [that] tells what, I think, is a really interesting story. It was a story that I thought was important in terms of civilization basically kind of destroying itself. I feel like it was eerily relevant, considering the current state of affairs here. [Laughs.] There's a real irony to seeing someone come from another planet to earth and say, "Okay, we’re going to make this our home." Like, if they only knew how many problems we have…

Sometimes indie films are annoying because there's not enough money and it seems like the budgets keep getting smaller and smaller. Financiers have figured out that they can get something from nothing, so they're always prudent. They give the least amount of money possible to get their film back. And then they pat themselves on the back. There's always sacrifices getting made. If you don't start with enough money then the film suffers. It happens all the time with some people. They run out of time or they don't have the resources they need to do something the way that they see it in their mind. But they've got to accept it because nobody's going to give them any money. It's sad sometimes. It seems like it didn't used to be that way.

Buy tickets now for Elvis & Nixon, Poor Boy, and Wolves.