BY THE EDITORS |

We Have Some Notes: Never Forget

“On that terrible day, a nation became a neighborhood, all Americans became New Yorkers.” – George Pataki

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIBECA’S LATEST NEWSLETTER

IT HAPPENED HERE

Here at Tribeca, we think of ourselves as part of a global citizenry and enthusiastic participants in a cultural conversation that transcends borders, languages, and differences. But every September 11th, we feel particularly bound to our home in downtown New York City, where one of the most horrific and unforgettable events in our nation’s history occurred.

Many of the particulars of the experience were disorienting: the clear blue sky that day, obscene in its beauty, and its subsequent vandalism, which left an acrid smell in the air for weeks after the towers fell. The vacuum in the city skyline where the World Trade Center had been, which seemed like a terrible illusion. And most of all, the otherworldliness our neighborhood took on as our grief and shock transmuted into a sense of belonging and solidarity anchored by place.

In the years since, we’ve come to view the events of 9/11 as a crucible–one that intensified our mission and our commitment to storytelling that reflects humanity in its fullness. A big part of why we started the Tribeca Film Festival was to bring people back to our neighborhood and help to restore the vibrancy for which our city is loved and known. Our first festival was a memorialization of September 11th, put together with over 1,300 volunteers from the community. We opened with a speech by Nelson Mandela, who said “The arts in general, and films in particular, represent some of the most powerful ways in which understanding and respect can be promoted.” Equally important, the arts helped us process our grief. Our co-founder Jane Rosenthal put it best: “We have to acknowledge what we’ve been through as a way of moving on… Movies help you feel better.”

I LAUGH BECAUSE I MUST NOT CRY

In the immediate week after September 11th, it was hard to embrace or trust anything that carried the tinge of normalcy, including entertainment. When could we laugh again? Would we ever? This dilemma was particularly discombobulating for people who enjoy and make comedy, but Jon Stewart was the first late night talk show host to confront what had happened, and he did it with great sensitivity. “There is no other way really to start this show than to ask you at home the question that we’ve asked the audience here tonight and that we’ve asked everybody that we know here in New York since September 11th,” he began “and that is, ‘Are you okay?’”

Stewart’s monologue holds up and is worth re-watching because it channels an emergent feeling New Yorkers–and really, the entire country–began to feel as we recovered from collective trauma: that we were resilient and that we would be okay, maybe even stronger than we were before. Stewart went on to become an activist who has worked to get first responders affected by 9/11 the healthcare benefits they deserve and you can follow his efforts in the documentary series No Responders Left Behind.

THE CENTER OF THE WORLD

As an architectural monument, the Twin Towers were both loved and loathed. They were iconic, a natural compass for orienting oneself in the city, and were at times derided as emblematic of American grandiosity. They were also an ambitious undertaking with distinctive civic ends. The buildings were part of a post-World War II vision to boost international commerce, a passion project of David Rockefeller’s, and a mechanism to inject lower Manhattan with the best features of urban life, and make it liveable and vibrant.

In 1983 PBS made an 18 minute film on the construction of the towers and you can view original footage of the tower being built.

Architect Minoru Yamasaki received a lot of criticism for the towers, much of which was racist and unfair, and his legacy is revisited in Justin Beal’s Sandfuture, which is part memoir and part examination of Yamasaki’s work. It’s original and novelistic, and thoughtfully considers how history is shaped by culture and who benefits and suffers.

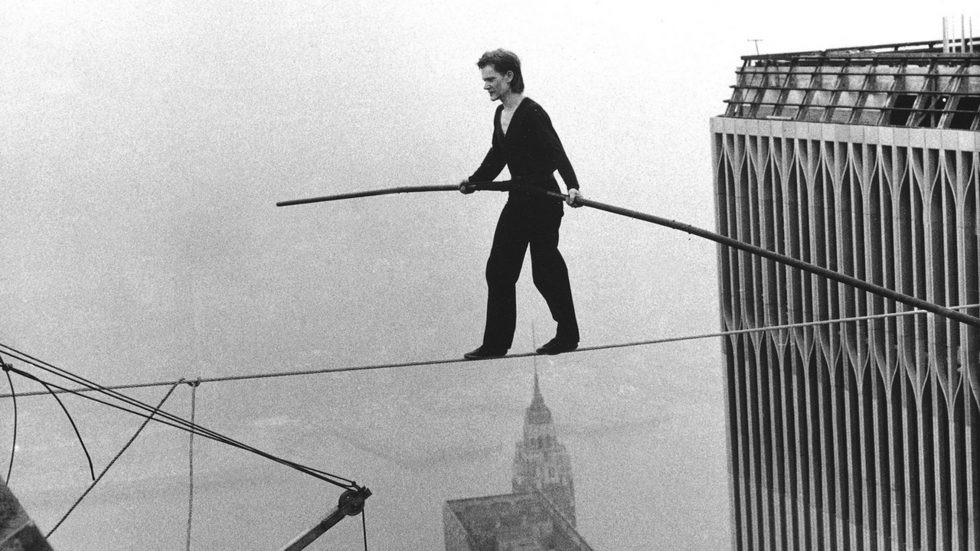

THE ARTISTIC CRIME OF THE CENTURY

Not to be missed: Man on Wire, a brilliant Oscar-winning documentary about Philippe Petit’s illegal tightrope walk 1,312 feet above the ground between the Twin Towers in 1974, a feat he referred to as “le coup”. He performed for 45 minutes and made eight passes. Filmmaker James Marsh chronicles Petit’s six years of meticulous planning with the pacing of a heist film. When we screened Man on Wire at the festival in 2008, Marsh said he hoped people would view the film as a gift to the city: a memory of the Twin Towers that would be beautiful.

WHAT WE’RE (RE-)READING

One of our favorite novels, and a great companion to Man on Wire, is Colum McCann’s wonderful Let the Great World Spin, which won the National Book Award. Set in 1970s New York, it opens with Petit’s performance and chronicles the lives of New Yorkers as they deal with the aftermath of Vietnam and the difficulties of surviving in the city, but it is ultimately a book about hope, and how a city marked by division can be drawn together by an act of beauty, and how art can heal.

Contemporary to McCann, fellow Irishman Joseph O’Neill wrote one of our other favorites, his debut novel, Netherland, which follows a group of immigrants who move to New York City after 9/11. It’s a story of what America means to the rest of the world and how strivers and idealists both complicate and exalt the idea of The American dream.

No Day Shall Erase You: The Story of 9/11 As Told at the National September 11 Museum is an official companion to the museum that now stands where the Twin Towers once were, assembled by the museum’s former Director, Alice Greenwald. Comprised of essays and photographs, it’s an important record of how 9/11 exists in our national memory, and continues to affect us in the present day.

For a another detailed non-fiction account of September 11th, Garrett M. Graff’s The Only Plane in the Sky: An Oral History of 9/11 is an exhaustive and poignant inventory of memories from people who were there. It’s a panoramic view of what happened drawn from interviews with nearly 500 people–government officials, first responders, New Yorkers and others–and an important reminder of the resilience and courage that often emerges in the face of unprecedented tragedy.

And finally, we leave you with Wislawa Szymborska’s short poem, “Photograph from 9/11.”

Every product is independently selected by editors. Items you buy through our links may earn us a commission.

Some Gospel for the Road

“In the end we can have our differences, even stereotypical attitudes toward each other, but once we are more aware, we get closer to realizing that we are no different from one another.”

- Robert De Niro