BY MATT BARONE |

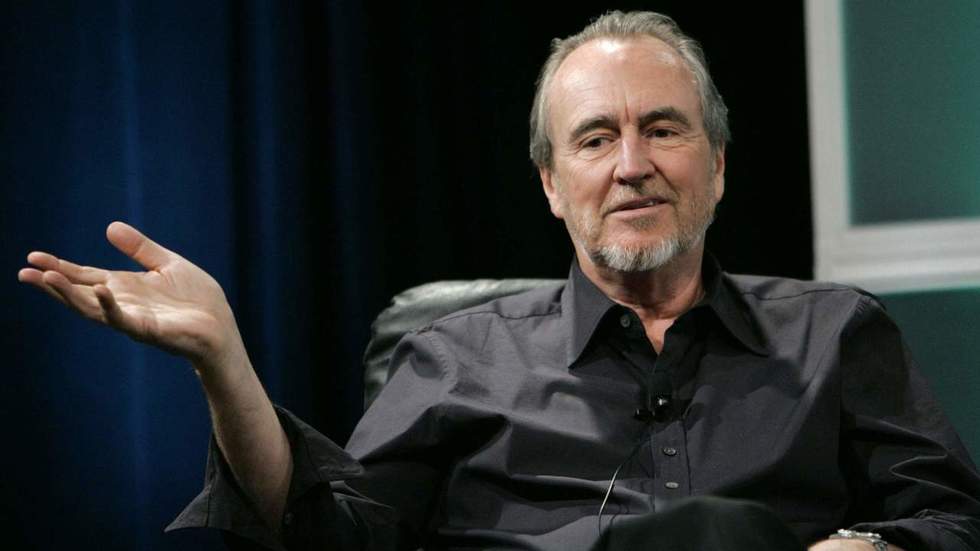

Master Class: How Wes Craven Reinvented the Horror Genre Three Decades in a Row

The horror world lost one of its all-time masters last night. Here, we take a look back at the remarkable ways in which Wes Craven continually redefined the genre for over 40 years.

The horror god had given many times, and now the horror god has been taken away.

The sole creative proprietor of the 2015 indie horror sensation It Follows is, of course, writer-director David Robert Mitchell, but even Mitchell would quickly admit that he and his film owe a great deal of the credit to one of the genre’s towering icons—and, no, in this case it's not John Carpenter, whose wide-angle suburban image and powerfully creepy synthesizer scores directly inspired and informed It Follows. Indeed, Mitchell turned to Carpenter for his film’s aesthetics, channeling the hypnotic photography and dread-coated atmospheres seen in Carpenter-made works like Halloween and The Fog. But It Follows' refreshingly original subversion of teenage horror makes it a down-the-line disciple of A Nightmare on Elm Street. The titular "It," an entity that takes the forms of various soullessly mobile and unstoppable marauders, is Mitchell’s sexualized answer to Elm Street's Freddy Krueger; the ways in which "It" uses teenagers’ promiscuity and mankind’s need for sex against Mitchell’s film’s characters mirrors how Krueger turned the unavoidable and uncontrollable act of sleeping into an inescapable homicide venue.

Mitchell’s film blessed horror with the most original mythology and supernatural agenda since, well, Elm Street. And now, four months after It Follows staked its claim as this generation's Elm Street, the latter’s brilliant creator has left this world far too early.

Last night, Wes Craven passed away from brain cancer. He was 76.

Fittingly, Mitchell joined the evening's lengthy chorus of Craven fans voicing their sadness over the news but, more importantly, deeply rooted appreciation for the man’s work on Twitter:

RIP Wes Craven pic.twitter.com/empseosNfa

— DavidRobertMitchell (@DRobMitchell) August 31, 2015Although he's no longer here, Craven’s horror masterworks will never age, nor will they ever die.

If there were ever to be a horror cinema Mount Rushmore variation, Craven’s head would be enormously sculpted right there whichever other three directorial giants any given horror fanatic chooses, whether it's James Whale, John Carpenter, George A. Romero and/or Dario Argento. While those other guys not named John Carpenter could be somewhat debatable, Craven's standing as one of the genre’s all-time greatest and most important filmmakers will never be up for discussion. Even Craven’s less-celebrated fan favorites (The People Under the Stairs, Shocker) and all-out misses (Deadly Blessing, My Soul to Take) are more interesting than most directors’ on-point movies.

He’s the only director, no matter which kind of movie is being evaluated, who managed to reinvent a genre in three separate decades. Looking back at the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, a horror expert wouldn’t be wrong in awarding Craven with each decade’s best movie: The Last House on the Left (1972), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and Scream (1996), respectively.

The funny thing is, though, that Craven never intended for his career to unfold in that way. Starting out as an editor and writer for low-rent porno movies in the early ’70s, Craven fell into the horror genre by chance, when his friend, and fellow porno maker, Sean Cunningham—who’d go on to direct the original Friday the 13th—asked his buddy Wes to direct the horror picture he’d been hired to help produce. More into societal unrest than creature features at the time, the novice Craven took Cunningham’s resources and shot an angry anti-Vietnam shocker disguised as a sleazy exploitation picture. As tough to watch and violently disturbing today as it was back in 1972, The Last House on the Left distinguished itself from the rest of its classifiable genre by being distinctly Craven's vision. The horror derives from everyday people, not ghosts or goblins; when the four-pack of depraved sadists at its center rape, humiliate and ultimately murder two teenage girls in an isolated forest, they eventually show remorse and look at their vile handiwork with a discomforting blend of fascination and disgust.

Craven didn’t want to make horror movies in the first place, so when he was tasked with doing just that, he delivered an anti-horror-movie horror movie, one that’s since been regarded as a defining moment of its decade and one of '70s cinema's most unforgettable displays of Vietnam-generated anger. In Craven’s generation’s collective mind, the soldiers dying overseas were losing their lives as needlessly and matter-of-factly as The Last House on the Left's two doomed young girls. To him, man’s ability to send youngsters to fight needless battles wasn’t far removed from a director subjecting ticket-buying audience members to an innocent teenage girl being forced to piss herself by her soon-to-be killer. That’s far scarier and more psychologically lasting than any fictional beast or demon. "The first monster you have to scare the audience with," Craven once said in an interview, "is yourself."

The Last House on the Left used horror as a means to blindsiding unsuspecting viewers with not only perversely repulsive imagery but also a socially conscious message. Four years earlier, he’d been knocked sideways by George Romero's Night of the Living Dead, a Civil Rights missive masquerading as a claustrophobic, zombie-packed nightmare. "[Night of the Living Dead] made me realize that with a genre film, as long as it scared you, you could say anything; about politics, about psychology," Craven told Rotten Tomatoes in a 2009 interview. "It made me realize as well that fear is one of the primary thresholds you experience things through."

When it came time to make his first movie, Craven found uncomfortable motivation in the infamous 1972 image of the naked little girl running down the street after a Napalm attack in the village of Trang Bang. "That was my coming of age to realizing that Americans weren't always the good guys," said Craven in the excellent 2000 documentary The American Nightmare, "and to the things that we could do could be horrendous or evil or dark, or impossible to explain."

Its technical grittiness and naturalistic performances aside, Romero's Night of the Living Dead took place within a heightened reality, one where the dead come back to quasi-life and eat human flesh. Craven’s The Last House on the Left, populated by real people doing ungodly things, signaled a change away from the genre's surface-level ghosts, monsters and reanimated corpses seen in the previous decades' films. And it did so by transferring the grotesqueries seen in Night of the Living Dead, as in zombies gnawing on intestines as if they're BBQ ribs, away from the make-believe. The Last House on the Left's moment where Krug (David Hess) shoots Mary (Sandra Cassel) as she drifts into the lake was a direct callback to, in Craven's own words, the 1968 photo of a Vietcong man being shot at point-blank range by a Saigon police chief. "It just seemed like there was nothing to be trusted in the establishment and everything to be trusted in yourself, and your generation," said Craven said in The American Nightmare, about the context in which Last House was made. "It's the film of a young man who had much more rage than he ever realized."

Fueled by those real-life atrocities, The Last House on the Left redefined horror’s nastiness, injecting the genre’s taboo-bashing side with a newfound intelligence and undeniable artistry—it was a tremendous step upwards from Blood Feast (1963) and Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), those similarly assaultive and icky films from the one-dimensional provocateur Herschell Gordon Lewis. Whereas Lewis’ exploitation filmmaking merely wanted to produce internal vomit, Craven’s wanted to sicken the mind.

Craven’s best films typify his cerebral approach to horror. After altering horror’s course in the '70s with The Last House on the Left, he made it a two-peat with A Nightmare on Elm Street, a slightly fantastical and all-the-way ambitious remixing of then-popular slasher film tropes. Following the hugely lucrative triumph of Craven’s old pal Sean Cunningham’s Friday the 13th, the film industry unsurprisingly began copying Jason Voorhees’ formula and cranked one slasher movie imitation after another. Aping Friday the 13th's simple yet fruitful template, those knockoffs sent a masked or deformed killer out to pick off good-looking teenagers one by one, and the genre, while certainly productive and highly entertaining in the eyes of carnage lovers, lost its scares because of that.

But then Craven brought genuine terror back with A Nightmare on Elm Street. The slasher checklist was intact—Elm Street’s dream-occupying Freddy Krueger pinpoints attractive studs and co-eds and offs them in hideously graphic ways, leaving the "final girl" there to take her friends’ murderer down by herself. Elm Street, though, proved that slasher movies, and, in turn, the horror genre as a whole, can be as smart and crafty as they are gruesome and corpse-ridden. He introduced a never-before-explored setting in which to push the genre’s boundaries (a person’s dreams, where they’re the most vulnerable); more importantly, Craven birthed an instantaneous horror icon in Freddy Krueger (played with amazingly nihilistic charm by Robert Englund), whose dynamic personality stood as a counterpoint to the silent-but-deadly likes of Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers. With Elm Street, Craven handled teenage horror with a deep respect for his audience’s intellect. They thought they were getting another elementary body-count film, but they instead received an antithetically elevated institution.

It takes a brainy risk-taker like Craven to rebel against the film game's laziest conventions with something as audacious as A Nightmare on Elm Street. Being that guys like Craven come a penny in a dozen, though, there aren’t many Elm Street-like cage-shakers out there. In 1996, Craven found himself in Cunningham's Friday the 13th shoes. Molding first-time screenwriter Kevin Williamson’s aggressively meta and wittily impressive Scream script into both a career reinvention and nothing like anything horror fans had seen before (despite what Quentin Tarantino thinks), Craven flipped the slasher sub-genre on its machete-sliced head by overtly manipulating the rules and scare-minded trickery that he’d abused post-Elm Street himself. Scream throws slashers' clichés and familiar beats under the bus—or, rather, Gail Weathers' news van—so daringly and effectively that slasher cinema has never truly been able to recover. Elm Street breathed new life into horror's stalk-and-kill mindset; Scream jammed a knife right through it and let all the air out.

And because there was, and always will be, only one Wes Craven, none of his peers or acolytes were able to repurpose Scream the way Craven did Friday the 13th. The years following Scream were filled with Hollywood-distributed rip-offs, like I Know What You Did Last Summer, Urban Legend and Valentine, that damn near decapitated the genre’s brain-housing cranium and left it for dead.

Horror’s new hopes didn’t arrive until around 2004. Dubbed the "Splat Pack," a group of young filmmakers from all over the world ignored the Scream crumbs and studio executives’ obsessions with remaking Japanese films like Ringu and The Grudge. Directors like France’s Alexandre Aja (High Tension) and America’s Eli Roth (Hostel, 2005) and Rob Zombie (The Devil’s Rejects, 2005) viciously sent horror back to the 1970s with their brutally hardcore films. They took inspiration from movies like Craven’s The Last House on the Left and woke the genre up from its overlong period of creative stasis. They openly acknowledged Craven as a major influence. Aja, in fact, parlayed his High Tension momentum into remaking Craven’s Last House follow-up, 1977's The Hills Have Eyes, in 2006. Craven, a fan of High Tension, even served as a producer.

The horror god who’d given 34 years earlier had given again, and directly to one of his biggest fans.

And Craven, a horror god if there ever was one, never stopped giving. He recently executive-produced The Girl in the Photographs, one of the most anticipated world premieres in the Toronto International Film Festival's genre-defining Midnight Madness program, which kicks off later this month. It's directed by Nick Simon, for whom Craven acted as a mentor at Los Angeles’ American Film Institute Conservatory in the mid-2000s. Always the generous and supportive elder statesman, Craven enthusiastically put his name behind Simon’s once-fledgling project, knowing that the "produced by Wes Craven" tag would drum up buzz and, ultimately, help Simon make the film.

The Girl in the Photographs now has the bittersweet honor of being Craven’s last film—as producer, director or otherwise. Before his passing, Craven made sure to let his 253,000 Twitter followers know about the film, too:

Proud to announce that The Girl in the Photographs is premiering @TIFF_NET. Congratulations @Simon367! Can't wait for you all to see it.

— Wes Craven (@wescraven) August 11, 2015Last night, Simon mourned his friend on the same platform:

Today we lost a legend. #wescraven was my mentor, collaborator and friend. My heart goes out to his family.

— Nick Simon (@Simon367) August 31, 2015The horror god may have been taken away, but his imprints will remain in films like The Girl in the Photographs, It Follows and the countless other future horror movies written and directed by Wes Craven’s admirers.

Without everything Wes Craven gave to it, the horror genre would be scary for all the wrong reasons.