BY MATT BARONE |

VINYL is the Wildest Martin Scorsese Movie That HBO Could've Ever Asked For

At nearly two hours long, the premiere episode of HBO's massive new '70s rock 'n' roll saga shows the god Marty Scorsese at his most wonderfully reckless.

There’s a moment of madcap nihilism in Vinyl’s pilot episode that’s up there with anything in The Wolf of Wall Street. The connection isn’t only tangential—HBO’s hugely ambitious new series, set in the drug-riddled cesspools and bearded extravagance of 1970s New York City’s vibrant music scene, is executive produced by Martin Scorsese, along with Mick Jagger, and is being overseen by Scorsese’s Boardwalk Empire captain Terence Winter, along with Breaking Bad alum George Mastras. And, like a gift from HBO to the cinema gods, Vinyl’s 112-minute-long pilot episode is directed by Scorsese himself. That’s right, HBO has essentially delivered a new Martin Scorsese movie underneath everyone’s constantly-sniffing-for-scoops noses, a down-and-dirty one that’s replete with, well, characters sniffing for lines with their noses. It’s Scorsese with his gloves off and his grittier '80s mentality back in effect.

That Wolf-like sequence comes near the pilot’s end, after writers Winter and Mastras have introduced the hell out of the show’s main character, the foul-mouthed, cocky, yet subtly vulnerable record label owner Richie Finestra, played amazingly by the always excellent Bobby Cannavale. Finestra is visiting a vulgar radio station owner named Buck Rogers (played with profane zeal by Andrew "Dice" Clay) who’s hopped up on cocaine and holding a handgun. Buck’s watching James Whale’s Frankenstein and listening to, that’s right, The Edgar Winter Group’s "Frankenstein." In a coke-fueled bender, Buck speaks like a madman and fires a bullet into the screen and through Boris Karloff’s forehead, in a kind of delirious self-defense. The scene then escalates into the caliber of Grand-Guignol-esque, tough-guys-gone-H.A.M. violence that Scorsese perfected in the gangster classics Goodfellas and Casino. It’s a comforting proclamation that Vinyl isn't playing around. In its own carnally minded way, it has the potential to be HBO's heir apparent to Game of Thrones.

It’s too soon to concretely give Vinyl those lofty props, but for now, just know this: Its tremendous pilot deserves placement alongside Scorsese’s best movies. It's that fully realized, that audacious, and that damn good.

Set in 1973, Vinyl looks and feels like it was made in that year as well. This is Scorsese rechanneling his Mean Streets points-of-view towards New York City. Through impressive set design work and undetectable CGI, New York City’s yesteryear griminess dominates nearly every frame, from the graffiti-decorated subway stations to nightclub hallways openly populated by women giving fellatio and freaky men with nipple-clamps. Vinyl’s pilot is bookended with a coked-out Richie’s impromptu visit to the seedy Mercer Arts Center, where, inside, he assimilates into a crowd of free-spirited, head-banging, and debauchery-obsessed youngsters deliriously rocking out at a kinetic New York Dolls show. Thanks to a potent combination of illegal narcotics and music-loving euphoria, Richie stands there in awe, his mouth agape as if he’s mimicking Sleepaway Camp’s insane final scene, his body motionless while everyone around him convulses in excitement.

It’s easy to imagine Scorsese reacting similarly the first time he read Winter and Mastras’ script. Narrated by Cannavale with the boisterous, curse-laden swag of Robert De Niro’s best Scorsese-movie voiceovers, Vinyl’s pilot plays like a Marty Greatest Hits compilation; while addressing viewers who might hate him for being filthy rich, Richie boasts, "Remember this, you jealous prick—I've earned my right to be hated." But there’s none of the too-on-the-nose pastiche such a descriptor might suggest. There’s even a bit where Andrew Dice Clay’s Buck Rogers snaps at Richie with a contentious retort reminiscent of Joe Pesci’s “You think I’m funny?” moment in Goodfellas. Cannavale's dialogue is razor-sharp; he rationalizes his biggest character flaw with, "I had a golden ear, a silver tongue, and a pair of brass balls, but the problem became my nose, and everything I put up it." With his colorful and revealing narration, he's an amalgamation of Goodfellas’ Henry Hill and Casino’s Sam Rothstein.

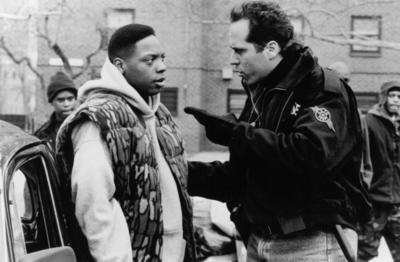

Its delightful Scorsese-isms aside, Winter and Mastras’ script is as intelligent as it is grandiose. Richie’s record label, American Century Records, is home to rock 'n' roll acts like Led Zeppelin and Donny Osmond; as Richie angrily tells a room full of complacent A&R’s, “Our goddamn roster is like a Chinese menu—it’s all over the fucking place!” But Winter and Mastras don't ignore one of the music industry’s least acknowledged facts: American music has been largely built on the creativity of overlooked black talent. Richie’s lowest moments of despair are complemented by flashbacks to the early ’60s, when he managed an upstart African-American blues guitarist named Lester Grimes (Ato Essandoh), got him a record deal, and then simultaneously abandoned and ruined him while bettering his own executive career. In 1973, Lester unexpectedly reenters Richie’s thought process after Richie unsuccessfully tries to inquire about the loud hip-hop music, courtesy of DJ Kool Herc, that’s coming out of Lester’s Bronx housing project.

Lester is one of several promising fixtures in Richie’s complicated world. The strongest is Amber Vine (Juno Temple), American Century’s sandwich-fetching A&R assistant who has zealous designs on show Richie that she’s invaluable. Early into the pilot, she finds the right struggling artist with whom to attach herself: an anti-establishment singer named Kip Stevens (James Jagger, son of Mick) who fronts an upstart punk band called the Nasty Bits and fights people in the crowd during their rowdy shows. It's a well-deserved big look for Temple, a gifted scene-stealer who's been relegated to thankless hooker/sexpot/must-get-naked roles in movies like Killer Joe, Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, and Black Mass and has consistently made those otherwise forgettable roles sing, like Adele covering Paris Hilton's Paris album. Vinyl is her 25.

All of these pieces, ferociously anchored by Bobby Cannavale, are putty in Scorsese’s jittery hands throughout Vinyl's inaugural episode. With its Caligula-rivaling, R-rated mayhem, The Wolf of Wall Street felt like the iconic master’s return to reckless old-school form, firing on all reckless cylinders and landing in direct opposition against the great yet palpably calculated Hollywood appeal of awards-baiting movies like The Departed and Hugo. But Scorsese's nearly two-hour-long Vinyl contribution feels even more gloriously unfettered than his Jordan Belfort biopic. Scorsese’s lifelong affinity for rock music has permeated through his documentary work, but in his narrative films, it’s mainly been confined to spot-on soundtrack choices, not storytelling impetuses. Vinyl allows him to run wild with those interests, and the pilot rollicks with such manic energy that you’d think it’s been orchestrated by the Scorsese of ’73, the then-31-year-old provocateur who was three years away from making Taxi Driver and living inhibition-free with living-on-the-edge friends/colleagues like John Milius and Paul Schrader.

As Cannavale's Richie basks in the Mercer Arts Center's uncontrollably combustive vibe during Vinyl’s pilot’s raucous closing sequence, his face contorting with animalistic pleasure at the sounds of rock 'n' roll's future, he might as well be the young Martin Scorsese’s surrogate. And as HBO’s viewers watch Vinyl’s triumphant premiere’s final minutes this Sunday night, they won’t want Godfather Marty to ever grow up again.

Vinyl premieres on HBO this Sunday, February 14, at 9 p.m. EST.